|

Our knowledge of ancient Egyptian is

the result of modern scholarship, for since the Renaissance, a symbolical

and allegorical interpretation was favored, which proved to be wrong.

The learned Jesuit

antiquarian Athanasius Kircher (1602 - 1680) proposed

nonsensical allegorical translations (Lingua Aegyptical restituta, 1643).

Thomas Young (1773 - 1829), the author of the undulatory theory of light, who had assigned the correct

phonetical values to five hieroglyphic signs, still maintained these alphabetical

signs were written together with allegorical signs, which, according to him, formed the bulk.

The final decipherment, starting in

1822, was the work of

the Frenchman Jean-François Champollion, 1790 - 1832, cf. Précis

du système hiéroglyphique des anciens égyptiens par M.Champollion le jeune,

1824.

Champollion, who had a very

good knowledge of Coptic (the last stage of Egyptian), proved the

assumption of the allegorists wrong. He showed (especially aided by the presence

of the Rosetta Stone) that Egyptian (as

any other language) assigned phonetical values to signs. These formed consonantal

structures as in Hebrew and Arabic. He also discovered that some were pictures

indicating the category of the preceding words, the so-called

"determinatives".

After Champollion's death in 1832, the lead in egyptology passed to Germany

(Richard Lepsius, 1810 - 1884). This Berlin school shaped Egyptian philology for

the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, in particular scholars such as Adolf

Erman (1854 - 1937), Kurt Sethe (1869 - 1934), who, together with Francis

Griffith (1862 - 1934), Battiscombe Gunn (1883 - 1950) and Alan Gardiner (1879 -

1963) in England, laid the systematic basis for the study of Egyptian. Later,

Jacob Polotsky (1905 -1991) established the "standard theory" of

Egyptian grammar.

These efforts finally made the historical record available to scholars

of other disciplines, so that through interdisciplinarity, the impact of

Pharaonic Egypt on all Mediterranean cultures of antiquity could be weighed. The

result being, that Ancient Egypt is no longer neglected in the history of the

formation of the Western intellect.

|

Chronology

approximative,

all dates BCE

Predynastic

Period

- earliest communities - 5000

- Badarian - 4000

- Naqada I - 4000 - 3600

- Naqada II - 3600 - 3300

- Terminal Predynastic Period : 3300 -

3000

Dynastic

Period

- Early Dynastic Period : 3000 - 2600

- Old Kingdom : 2600 - 2200

- First Intermediate Period : 2200 -

1940

- Middle Kingdom 1940 - 1760

- Second Intermediate Period : 1760 -

1500

- New Kingdom : 1500 - 1000

- Third Intermediate Period : 1000 - 650

- Late Period : 650 - 343

|

In order of difficulty, the reader may study the following recent books &

dictionaries to be able to read classical Egyptian, i.e. hieroglyphic

Middle Egyptian. When this is acquired, a large section of the literature can be

directly addressed. Middle Egyptian was first introduced in the Middle Kingdom

and used in religious contexts until the Late Period (italics refer to the

presence of outdated entries or grammar) :

-

Davies, W.V.

: Reading the Past : Egyptian Hieroglyphs, 1987.

-

Hiéroglyphes

: écriture et langue des Pharaons, CD-Rom, Khéops - Paris, 2001.

-

Colling, M.

& Manley, B. : How to read Egyptian hieroglyphs, 2001.

-

Gardiner,

A. : Egyptian Grammar, 1982.

-

Du Bourguet,

P. : Grammaire Egyptienne, 1980.

-

Lefebvre,

G. : Grammaire de l'Égyptien classique, 1955 (2 volumes).

-

Allen, J.P. :

Middle Egyptian, 2000.

-

Budge,

E.A.W. : A Hieroglyphic Vocabulary to the Book of the Dead, 1911.

-

Budge,

E.A.W. : An Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary, 1920 (2 volumes).

-

Erman, A. :

& Grapow, H. : Aegyptisches Handwörterbuch, 1921.

-

Faulkner,

R.O. : A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian, 1972.

-

Van der Plas,

D. : Coffin Texts Word Index, 1998.

-

Hannig, R. : Ägyptisches

Wörterbuch I, 2003.

The first

hieroglyphs of the Egyptian language, often attached as labels on commodities, were written

down towards the end of the terminal predynastic period (end of the fourth

millennium BCE).

There is a continuous recorded until the eleventh

century CE, when Coptic (the last stage of the language) expired as

a spoken tongue and was superceded by Arabic.

Egyptian knew six stages :

Archaic Egyptian (first two Dynasties), Old Egyptian (Old Kingdom), Middle

Egyptian (First Intermediate Period & Middle Kingdom), Late Egyptian (New Kingdom & Third

Intermediate Period), Demotic Egyptian (Late Period) and Coptic (Roman Period).

In the last two stages, new scripts emerged and only in Coptic is the

vocalic structure known, with distinct dialects. Archaic Egyptian

consists of brief inscriptions. Old Egyptian has the first continuous

texts. Middle Egyptian is the "classical form" of the language.

Late Egyptian is very different from Old and Middle Egyptian (cf. the

verbal structure). Although over 6000 hieroglyphs have been documented,

only about 700 are attested for Middle Egyptian (the majority of other

hieroglyphs are found in Graeco-Roman temples only).

Egyptian hieroglyphs is a system of writing which, in its fully developed

form, had only two classes of signs : logograms and phonograms.

logogram (word writing)

A logogram is the representation of a complete word (not individual

letters of phonemes) directly by a picture of the object actually

denoted (cf. the Greek "logos", or "word"). As

such, it does not take the phonemes into consideration, but only the

direct objects & notions connected therewith.

For example :

, depicting the sun, signifies :

"sun", is a logogram , depicting the sun, signifies :

"sun", is a logogram

, depicting a mouth, signifies :

"mouth", is a logogram , depicting a mouth, signifies :

"mouth", is a logogram

A writing system exclusively based on logography would have thousands of

signs to encompass the semantics of the spoken language. Such a large

vocabulary would be unpractical. Moreover, which pictures to use for

things that can not be easily pictured ? How to address grammatics ?

phonogram (sound

writing)

Egyptian phonography (a word is represented by a series of

sound-glyphs of the spoken sounds) was derived through phonetic

borrowing. Logograms are used to write other

words or parts of words semantically unrelated to the phonogram but with

which they phonetically shared the same consonantal structure.

For example

:

The logogram  , signifies

"mouth". It is used as a phonogram with the phonemic value

"r" to write words as "r", meaning "toward"

or to represent the phonemic element "r" in a word like

"rn" or "name". , signifies

"mouth". It is used as a phonogram with the phonemic value

"r" to write words as "r", meaning "toward"

or to represent the phonemic element "r" in a word like

"rn" or "name".

"rn" or "name" : the

logograms of mouth and water "rn" or "name" : the

logograms of mouth and water

This pictoral phonography is based on the principle of the rebus : show

one thing to mean another. If, for example, we would write English with

the Egyptian signary, the word "belief" would be written with

the logograms of a "bee" and a "leaf" ... The shared

consonantal structure allows one to develop a large number of phonograms.

They are the solid architecture of the language. In Egyptian, the

consonantal system was present from the beginning.

Three main categories

of phonograms

prevailed :

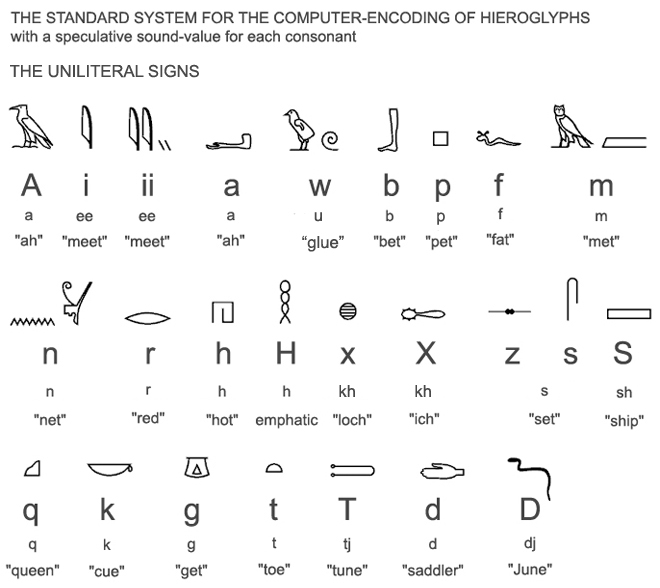

-

uniconsonantal

hieroglyphs : 26 (including

variants) - they represent a single consonant and are the most

important group of phonograms ;

-

biconsonantal

hieroglyphs : a pair of successive consonants (ca. 100) ;

-

triconsonantal

hieroglyphs : three successive consonants (ca. 50).

The last two categories are

often accompanied by uniconsonantal hieroglyphs which partly or completely

repeat their phonemic value. This to make sure that the

complemented hieroglyph was indeed a phonogram and not a logogram and/or

to have some extra calligraphic freedom in case a gap needed to be filled

...

This phonography allowed a

word of more than one consonant to be written in different ways. In

Egyptian, economy was exercized and spellings were relatively

standardized, allowing for variant forms for certain words only.

ideogram or semogram

(idea writing)

Logograms are concerned with direct meaning and sense, not with

sound. Likewise, Egyptian used so-called "determinatives",

derived from logograms, and placed them at the end of words to

assist in specifying their meaning when uncertainty existed.

A stroke for example was the determinative indicating that the function of

the hieroglyph was logographic. The determinative specified the

intended meaning. Some were specific in application (closely connected

to one word), while others identified a word as belonging to a certain

class or category (the generic determinatives or taxograms).

Determinatives of a word would be changed or varied to introduce nuance.

The same hieroglyph can be a logogram, a phonogram and a determinative.

For example :

The logogram  , depicting the sun, signifies :

"sun" (in continuous texts, a stroke would be put underneath the

hieroglyph to indicate a purely logographic sense). Placed at the end of

words, it is related to the actions of the sun (as in "rise",

"day", "yesterday", "spend all day",

"hour ", "period") and so the hieroglyph is a determinative.

In the context of dates however, it is a phonogram with as phonetic

value "sw". , depicting the sun, signifies :

"sun" (in continuous texts, a stroke would be put underneath the

hieroglyph to indicate a purely logographic sense). Placed at the end of

words, it is related to the actions of the sun (as in "rise",

"day", "yesterday", "spend all day",

"hour ", "period") and so the hieroglyph is a determinative.

In the context of dates however, it is a phonogram with as phonetic

value "sw".

Besides these purely semantical functions, the determinatives also marked

the ends of words and hence assisted reading. They helped to identify the

"word-images" in a text. Once established, these were slow to

change, causing, as early as the Middle Kingdom, great divergences between

the written script, becoming increasingly "historical", and the

spoken, contemporary pronunciations.

Logograms and determinatives are both ideograms. Pictoral ideography (a variety of

hieroglyphs representing idea's, notions, contexts, categories, modalities or

nuance's) conveys additional meaning. Ideograms are purely semantical (or semograms).

To the objective sound-glyph (the phonetics, in this case, being the consonantal

structures with no vocalizations) an ideogram is added changing the

overall meaning.

Hieroglyphic writing remained a consonantal, pictoral system, allowing for

both phonograms and ideograms to convey meaning.

Ante-rational cognition and Archaic, Old and Middle Egyptian.

modes

of thought |

examples

in Egyptian literature |

major

stages of growth in the formation of Middle Egyptian |

mythical :

sensori-motoric |

Gerzean ware design schemata,

early palettes |

individual

hieroglyps, no texts, no grammar, cartoon-like style

|

pre-

rational :

pre-operatoric |

Relief

of Snefru, Biography of Methen, Sinai

Inscriptions, Testamentary Enactment

Pyramid

Texts |

individual

words with archaic sentences, a very rudimentary grammar applied to simple sentences in the

"record" style of the Old Kingdom

|

proto-rational :

concrete

operations |

Maxims of Ptahhotep, Coffin Texts, Sapiental literature, ...

Great Hymn to

the Aten ...

Memphis Theology |

from

simple sentences to the classical form of a literary language capable of

further change and refined meanings

|

►

mythical writing

• Neolithic Period

Before the differentiation between the spoken and the written language, no

identification and transmission of meaning was possible, except through oral

means. Insofar as the ability to identify conscious activity was concerned,

only anonymous cultual productions prevailed. Mythical memory produced its

tales, legends and typical designs. No individual consciousness can be

denoted. The differentiation between, on the one hand, nature and its

processes and, on the other hand, human consciousness is very small or

completely absent. The graven images found in graves, point to the start of

the first decentration and the rise of the idea of objectifying meaning in

picture-glyphs (beginning of logography ?).

• Middle to Terminal Predynastic - Archaic Egyptian

This slow process of objectification gave rise to the experience of spatiality

: navigation on the Nile and the emergence of cult centers and urban

centers, associated with chiefdoms, principalities,

provincial states and village corporations, finally united into regional kingdoms.

Trade continued to flourish and wealth distinctions became more salient. The

subject experienced itself for the first time as

source of cultural actions. Differentiation (between object

and subject) led to logico-mathematical structures, whereas the

distinction between actions related to the subject and those related to the

external objects became the startingpoint of causal relationships. The

grammar of ware design is used, allowing for the decentration of actions with

regard to their material origin, for now myths could be recorded in schemata

which could be objectified by later subjects. The linking of objects was also

evident. Means/goals schemata rose. The dependence between the external

object and the acting body was mediated by elementary rules of design and

cultural dressing. These schemata led to spatial & temporal

permanency.

This process of interiorization (starting with the first decentration

and ending with the exhaustion of the mythical mode of thought) led in the

terminal predynastic period to an entirely new subjective focus which

exteriorized itself in single hieroglyphic writing. This event defined

the most important breach with the past : the end of the exclusivity of the

mythical mode of thought and its already complex spoken language and the start

of the history of Ancient Egypt. The advent of political unification is

consistent with this radical change.

In the mythical "first time" (zep tepy), the "primordial hill"

(benben)

emerged out of the undifferentiated. In the passive principle (Nun), the

active (Tatenen) lay dormant. In the resulting Ennead, 4 feminine & 4

masculine deities formed a balanced Ogdoad + a "Great

One" (Atum or Re or Ptah or Thoth or Amun-Re). The active pole drew its

"force" out of the balanced passive Ogdoad (reminiscent of the

pre-creational primordial Ogdoad of chaos-deities - cf. Hermopolitan

theology).

The final unification of the Two Lands became possible thanks to the

centralizing, masculine role of Pharaoh and his justice & truth. He was the

falcon who oversaw everything, the witnessing eye. Instead of the

emergence of conscious focus out of the inert, there came the conscious

awareness drawn from the panoramic overview. This presence of the

"Followers of Horus", was like the divine-on-earth (not the

divine-in-the-sky). The masculine is not drawn from (or constructed upon) the

feminine (as in the natural order), but the feminine is assimilated by the

masculine (as in the cultural order). The "onanism" of Atum may

also

be linked with this connotative field, for masturbation does not serve

procreation (neither does taking seed in one's mouth). The proto-typical battle

between Horus and Seth is one in which the feminine is totally absent.

This formidable political unification needed its landmarks. The

"Followers of Horus" became divine ancestors. They had to create a

material blueprint of their presence. The divine power of words being very

firmly established, no elaborate hieroglyhic writing was called upon. A few

signs in stone sufficed.

The rise of semiotics transformed the

sound-glyph into logograms & phonograms. The fact phonograms and logograms

were used in an outstanding, monolithic

way (hand in hand with artistic pictoral representations) shows the need to

exteriorize, in heraldic fashion, this collosal attainment around 3000 BCE (unification) and the foundation of the

Dynastic Age (Dynasty I

& II).

►

pre-rational

writing

• Early Old Kingdom (Dynasty

3 - 5) - Old Egyptian

When the difference between subject and object became a sign, a

higher mode of cognition could be expressed. This involved the written

language to realize its first internal structure, so words could be joined

together in simple sentences.

Internalization led to the formation of pre-concepts, i.e. word-images created

through imagination and the interplay of meaningful objective relational

contexts. Subjectivity was expressed as a function of an objective state. The

actions of the "I"-form are objective states which are not yet (self)

reflective. The opacity of the material side of presence prevailed. The

subject has no transparancy of its own.

The Relief of Snofru (first Pharaoh of Dynasty IV, ca. 2600-2571) shows

Pharaoh with the Atef-crown and upraised war-club (hedj) about to smite a Bedwi, whom

he has forced to kneel, holding him by the hair of his head. During Snefru's

mining operations in the Sinai, he probably had to battle with the Bedwin of

the region. The inscriptions accompanying the relief contain only titles and

attributes of Pharaoh. It reads :

"King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Favorite of the Two

Goddesses, Lord of Truth, Golden Horus : Snefru, Great God, who is given

satisfaction, stability, life, health, all joy forever. Horus : Lord of Truth. Smiter of Barbarians."

Sinai Inscriptions of Snofru, rock-walls

of the Wadi Maghara in the Peninsula of Sinai and palace façade (the

"banner"), translated by :

Breasted,

2001, p.75, § 169.

The earliest biography is of Methen, who died in the reign of Snefu, but

who's affiliations were with the preceding Pharaohs. His was the story of the

gradual rise of a scribe to overseer of provisions, and governor of towns and

districts in the Delta. He also was deputy in the eastern part of the Fayum

and the 17th Anubis nome (Upper Egypt). He was amply rewarded and tells the

reader about the size of his house with an account of the grounds. He was buried

near the terraced pyramid of Zoser of the earlier part of Dynasty III.

An

excerpt :

"He was made chief scribe of the provision

magazine, and overseer of the things of the provision magazine. He was made

(...) becoming local governor of Xois, and inferior field-judge of Xois. He

was appointed judge, he was made overseer of all flax of the king, he was made

ruler of Southern Perked and deputy, he was made local governor of the people

of Dep, etc ..."

Biography of Methen,

from his mastaba-chamber in Sakkara, Berlin Nos.1105-1106, translated by :

Breasted,

p.77, § 172.

In 400 years, the written language had considerably developed. But although

words could be joined together in simple sentences and the latter in

pragmatical groups (dealing with honors & gifts, offices, legacies,

inventories, testaments, transfers, endowments, etc.), the additive, archaic quality of

the style remained. The composition between these groups was loose or absent.

Subjectivity was still objectified. Pre-operatoric activity is limited by the

immediate material context. Writing reflected the part one had played in the

state.

The Pyramid Texts have their own particular problems and difficulties.

They are a set of symbolical "heraldic" spells

mainly dealing with the promotion of Pharaoh's welfare in the afterlife. These

spells were recited at various ceremonies, mostly religious and especially in

connection with the birth, death, resurrection and ascension of Pharaoh. These

texts are to a large extent a composition, compiling and joining of earlier

texts which circulated orally or were written down on papyrus a couple of

centuries earlier. Some of them go back to the oral tradition of the Predynastic

era, for they suggest the political context of Egypt before its

final unification. The relative rarity of corruptions is another

important fact making their study rewarding.

However, these texts are pre-rational because they are an amalgam of thoughts

in which contradictions occur which are left intact (between the Heliopolitan and Osirian elements). In harmony with the writing practice of the Egyptians,

older structures were mingled with new ones and many traces of earlier periods

remained. The extent with which this layeredness took shape is rather

pronounced. The language itself has the style of the "records" of

the Old Kingdom, often additive and with little self-reflection (which

starts with the First Intermediate Period). These Pyramid Texts are the

culmination of pre-rationality.

"While there is

some effort here to correlate the functions of Re and Osiris, it can hardly be

called an attempt at harmonization of conflicting doctrines. This is

practically unknown in the Pyramid Texts. (...) But the fact that both

Re and Osiris appear as supreme king of the hereafter cannot be reconciled,

and such mutually irreconcilable beliefs caused the Egyptian no more

discomfort than was felt by any early civilization in the maintenance of a

group of religious teachings side by side with others involving varying and

totally inconsistent suppositions. Even Christianity itself has not escaped

this experience." -

Breasted,

1972, pp.163-164.

In this collection, no epics or drama

is to be found. Didactic poetry (precepts) and lyrics in which personal

emotions & experiences are highlighted are nearly absent. The texts mainly

deal with religious & political literature. One of the common forms

of this literature was the litany-like scheme. We also find hyms & songs of

triumph. Stylistically, the texts reveal that parallelism and paranomia are

numerous. Various types of parallelism can be observed : synonymous (doubling

or repetition), symmetrical, combined, grammatical, antithetic, of contrast,

of constraint, of analogy, of purpose and of identity. Metrical schemes of

two, three, four, five, six, seven or eight lines occur (the fourfold being

the most popular). The play of words is the commonest literary feature and

depends on the consonantal roots of the words. Alliteration, metathesis,

metaphors, ellipses, anthropomorphisms and picturesque expressions are also

found.

►

early proto-rational writing

?

• Late Old Kingdom (Dynasty 6) - Old Egyptian

The administration of the Pharaonic State

was considerable. The need to develop the language rose.

In the Old Kingdom, we see the rise of three independent literary genres :

religious poetry, sapiental instructions and the biography. The literary style

of the period reflects the tranquil security of and unshaken faith in the

power of kingship.

At a certain point,

these realized interiorizations became operations, allowing for transformations. The latter make it

possible to change the variable factors while keeping others invariant.

Conceptual and relational structures arise. We see an increase in the formation

of coordinating conceptual structures capable of becoming closed

word-images by virtue of a

play of anticipative and retrospective constructions of thought (imaginal

thought-forms). This anticipation is clearly attested in the legal

documents. Retrospection was also firmly established.

A good example of this early proto-rational writing are the

Maxims of Ptahhotep. Here the rhetorical device of playing with words

having identical consonantal skeletons was used. In other texts, identical

grammatical formulæ are repeated, and ready made groups of word-images are

used.

"Ensuite, il faut avouer qu'à notre goût la

composition paraît décousue. Des conseils de civilité puérile et

honnête voisinent avec des fines remarques psychologiques. Mais si la forme

de notre exprit exige une organisation rationnelle et un classement de

matières, l'alternance de conseils de politesse et une tentative, requérant

l'effort, pour modifier son propre caractère, est peut-être pédagogiquement

excellente et résulte d'une grande expérience de l'enseignement."

Daumas,

1987, p.354, my italics.

The Middle Egyptian of this and other text from Dynasty VI (cf. the Instructions

of Kagemni), may be explained as resulting from only minor alterations, for

the end of Dynasty VI and the beginning of Dynasty XI are only a hundred years

apart. Moreover, many of the forms characteristic of Middle Egyptian are

found in the biographical inscriptions from Sixth Dynasty tombs. Dynasty

VI is hence transitional. Also politically, for the importance of the

provinces had risen, preparing the great changes introduced in the First

Intermediate Period and in the Middle Kingdom.

In the Discourse of a Man with his Ba

and the Complaints

of Khakheperre-sonb the acquired introspection leads to inner dialogues

(in the first work between the "I" and its "soul", in the

second between the "I" and its heart).

►

advances in proto-rational writing

•

First Intermediate Period and Middle Kingdom

- Middle Egyptian

The increase of individuality forced the language to

acquire more reflective capacities. The formal system underlying it became more complete. All necessary word-images were present and a variety of

literary styles existed (religious, funerary, legal, sapiental, poetic, prose,

etc.). The classical form of the language could already be sensed in the

Maxims

of Ptahhotep

(late VIth Dynasty), and the

Discourse of a Man with his Ba

(First Intermediate Period) but clearly emerged

in works like the Instruction to Merikare (XIIth Dynasty), the Prophecies of Neferti

(XIIth Dynasty), the Eloquent

Peasant (XIIth Dynasty), the Admonitions of

Ipuwer (late XIIth Dynasty), the Story of Sinuhe (late XIIth

Dynasty) ...

Constructive abstraction, new,

unifying grammatical and semantical coordinations allowed for the emergence of

a total system and

its auto-regulation (or the re-equilbration caused by perfect regulation). That mental operations

were

"concrete", not "formal", i.e. they exclusively appeared in immediate contexts,

is evidenced by the inability of the writing to realize a system which :

Furthermore, the position

of a noun in the sentence determined whether it was the subject or the object of a

verb. The normal word order being : verb + noun-structure + noun-object.

Complex sentences (with more than one subsentence) were rare, and the meaning

of a sentence could only be derived one step at a time.

This concrete, proto-rational writing contained a paradox : a balanced

development of logico-mathematical operations was evident, but the limitations imposed

upon the concrete linguistic operations pushed the language to move beyond

this.

The Story of Sinuhe shows the complexity arrived at. The

composition contained a lot of variety : narration, hymn, epic, monologue,

dialogue, copy of a royal letter and epistle-like response with stereotypical

expressions ... This work is also a psychological novel, explaining the

adventures of its hero on the basis of his character. The style of the writing

is of an elegant simplicity and the verbal forms have been carefully chosen.

The narrative style is organized by rhythmical prose using parallelism and

constituting a veritable religious song.

•

New Kingdom

- Late Egyptian

Late Egyptian introduced considerable grammatical changes. As a result, the

differences between Late Egyptian and Classical Egyptian are as considerable

as those existing between modern French and Latin, although the literary

genres remained unchanged (with greater originality though) ...

The verbal structure developed, but the pictoral, consonantal and ideographic

limitations were kept in place. Just like the New Solar Theology was able to

naturalize the deities without eliminating the old pantheon, so were

new linguistic innovations introduced side by side the "old"

language. This conservative tendency was one of the chief causes of the

layeredness of the language and suited the "multiplicity of

approaches" (cf. Frankfort) extremely well. Old forms (although

syntactically problematic) were retained because of the divine nature of words

and the idealization of the Old Kingdom. In the New Kingdom as well as in the

Late Period, archaism were savoured because the ancient word-images were

believed to arouse the Kas of old and hence provide the necessary magical

succession. To change a pattern for formal reasons was deemed less important

than to maintain a wrong combination which had proven its magical merits.

We therefore see in pre-rational writing the remnants of mythical thought at work,

and this by virtue of its psychomorph features. The presence of Predynastic material in the pre-rational Pyramid

Texts is attested. In proto-rational writing, these confusions were at times

left behind (cf.

Great Hymn to the Aten). Amarna

theology banished the old pantheon. Only the light-presence of the Aten,

absolutely alone, was divine, just as Pharaoh, son of the Aten, receptacle of

the revelations of the Aten and teacher. However, after Amarna, the ante-rational confusion of object & subject was restored (together with its

foundational mythical identifications) and the plurality of contexts was never

conceptually transcended by means in a theoretical form.

Insofar as Ancient Egyptian civilization as a whole is concerned, the

decontextualization of meaning in an abstract theoretical form never took

place. The language remained layered and archaic elements were sometimes

introduced or copied to give the text a feeling of antiquity (for that

reason, the

Memphis Theology

was

regarded as an

Old Kingdom text). Pictoral representations elucidating the text remained in

place (cf. the

vignette), as well as a type of ideogram called

"orthogram" or "calligram", which conveyed neither meaning

nor sound but was written for aesthetic reasons & pleasure. The cultural

form of Ancient Egyptian civilization remained at the level of the concrete

operations.

Summarizing :

-

Archaic

Egyptian = mythical :

the myth of divine writing - single hieroglyphs as divine passage-ways to

the divine - cartoon-like messages (pictures accompanied by logograms &

phonograms). This phase ends with single inscriptions without grammar,

culminating in loose pictoral narratives assisted by a few phonograms

(Palette of Narmer).

-

Old

Egyptian = pre-rational & early proto-rational

: the actual initiation of writing - written monuments for practical

purposes - the first pre-rational linguistic structures appear - single

sentences with simple forms - the emergence of contextualizing

determinatives - beginning of anticipation & retrospection - single

word-images forming groups which convey a particular style - the

differentiation of literary genres - sapiental writings. This phase ends

(in the late VIth Dynasty) with sentences in a particular style, able to

convey in a short and laconical way insights of incredible depth (Maxims of Ptahhotep).

-

Middle

Egyptian = proto-rational

: the formation of the classical form - interiorization leading to a

stable, self-reflective first person singular - object & subject

conceptually & relationally distinguished - verbal structures and the form

of sentences allow for greater nuance and poetry - the explosion of

literature and a further differentiation of the literary genres. This

phase ends with sentences and styles competing with the classical

literatures of all times. The classical form was flexible enough to change

even further in the New Kingdom (Late Egyptian). However,

proto-rationality was never superceded ...

Chronology

in BCE |

Pharaonic

Dynasties |

the Two

Lands |

Stages

of

Egyptian |

Modes |

Stages

of

Piaget |

|

ca.3600 |

none |

Gerzean |

schemata |

mythical |

sensori-

motoric |

|

ca.3300 |

none |

Terminal

Predynastic |

|

ca.3000 |

I and II |

Archaic

Period |

archaic |

pre-

rational |

pre-

operational |

|

ca.2600 |

III - IV |

Old

Kingdom |

old |

|

ca.2400 |

V |

|

ca.2300 |

VI |

|

ca.2200 |

VII - XI |

First

Intermediate Period |

middle |

proto-

rational |

operational

and

concrete |

|

ca.1940 |

XII |

Middle

Kingdom |

|

ca.1760 |

XII - XVII |

Second

Intermediate Period |

|

ca.1500 |

XVIII - XX |

New

Kingdom |

late |

|

ca.1000 |

XXI - XXV |

Third

Intermediate Period |

|

664 |

XXVI -

XXX |

Late

Period |

Besides the general principles developed in the context of my study of

Flemish

mysticism, namely the

Seven

Ways of Holy Love

of Beatrice of Nazareth (1200 - 1268), and the last part

of the Spiritual Espousals by Jan of Ruusbroec (1293 – 1381), called

The

Third Life, Ancient Egyptian

literature calls for special

considerations :

-

semantic

circumscription (Gardiner) : to those unaware of the semantical problem in

mythical, pre-rational and proto-rational thought and its literary products,

the differences between various translations may be disconcerting. Ancient

Egyptian literature is a treasure-house of this ante-rational cognitive

activity, and its "logic" is entirely contextual, pictoral,

artistic and practical. The meaning or conception of the sense of certain

words, especially in sophisticated literary context, is prone to large

discrepancies. Gardiner spoke of "interpretative preferences" (Gardiner,

1946). Furthermore, despite major grammatical discoveries, Egyptian writing

is ambiguous qua grammatical form. Some of its defects can not be overcome

and so a "consensus omnium" among all sign interpreters is

unlikely. The notion of "semantic circumscription" was derived

from this quote by Gardiner : "If the uncertainty involved in such

tenuous distinctions awake despondency in the minds of some students, to

them I would reply that our translations, though very liable to error in

detail, nevertheless at the worst give a roughly adequate idea of what the

ancient author intended ; we may not grasp his exact thought, indeed at

times we may go seriously astray, but at least we shall have

circumscribed the area within which his meaning lay, and with that

achievement we must rest content." (Gardiner,

1946, pp.72-73, my italics). To the latter, more attention to lexicography

(a discussion of individual words) and the rule that at least one certain

example of the sense of a word must be given were considered as crucial.

Personally, I would add the rule that one has to take into consideration all

hieroglyphs (also the determinatives) and try to circumscribe the meaning by

assessing the context in which words and sentences appears ;

-

the benefit

of the doubt (Zába) : amendments should be introduced with great caution

and for very good reasons. Indeed, some egyptologists change the original

text with great ease, considering Egyptian scribes to be careless and

prone to mistakes. This is not correct.

Zába

(1956, p.11)) prompted us to respect the original text and made it his

principle. He wrote : "Pour ce qui est la traduction d'un texte

égyptien dans une langue moderne, l'étude de divers textes (...) m'a amené

au principe dont je me suis fait une règle, à savoir de considérer a

priori un texte égyptien comme correct et de m'en expliquer chaque

difficulté tout d'abord par l'aveu de ne pas connaître la grammaire ou le

vocabulaire égyptien aussi bien qu'un Egyptien. (...) et ce n'est donc

qu'après avoir longement, mais en vain, consulté d'autres textes et ne

pouvant expliquer la difficulté autrement, que je suis enclin à croire que

le texte est altéré."

-

multiple

approaches (Frankfort) : this notion implies one has to assimilate the

Egyptian way of thinking before engaging in explaining anything. Their

"method" not being linear, axiomatic (definitions & theorema)

or linea recta.

Frankfort

(1961, pp.16-20)

explains : "... the coexistence of different correlation of

problems and phenomena presents no difficulties. It is in the concrete

imagery of the Egyptian texts and designs that they become disturbing to us

; there lies the main source of the inconsistencies which have baffled and

exasperated modern students of Egyptian religion. (...) Here then we find an

abrupt juxtaposition of views which we should consider mutually exclusive.

This is what I have called a multiplicity of approaches : the avenue of

preoccupation with life and death leads to one imaginative conception, that

with the origin of the existing world to another. Each image, each concept

was valid within its own context. (...) And yet such quasi-conflicting

images, whether encountered in paintaings or in texts, should not be

dismissed in the usual derogatory manner. They display a meaningful

inconsistency, and not poverty but superabundance of imagination. (...) This

discussion of the multiplicity of approaches to a single cosmic god requires

a complement ; we must consider the converse situation in which one single

problem is correlated with several natural phenomena. We might call it a

'multiplicity of answers'."

-

integral

acceptation (Zimmer) : in his study of Eastern religions and exegesis of

Hindu thought, the German scholar Heinrich Zimmer introduced a principle

which implies that before one studies a culture one has to accept it

exists or existed as it does and claims. One should approach and interprete

its cultural forms as little as possible with standards which does not fit

in, which focus on subjects which were of no interest to it (like the colour

of the hair of royal mummies) or which reduces it to what is already known.

This means one, as does comparative cultural anthropology with its

methodology of participant observation, accepts the culture at hand without

prejudices and projections.

Zimmer

(1972,

p.3) explains himself :

"La méthode -ou, plutôt, l'habitude- qui

consists à ramener ce qui n'est pas familier à ce que l'on connaît bien,

a de tout temps mené à la frustration intellectuelle. (....) Faute d'avoir

adopté une attitude d'acceptation, nous ne recevons rien ; nous nous voyons

refuser la faveur d'un entretien avec les dieux. Ce n'est point notre sort

d'être submergés, comme le sol d'Egypte, par les eaux divines et fécondantes

du Nil. C'est parce qu'elles sont vivantes, possédant le pouvoir de faire

revivre, capables d'exercer une influence effective, toujours revouvelée,

indéfinissable et pourtant logique avec elle-même, sur le plan de la

destinée humaine, que les images du folklore et du mythe défient toute

tentative de systématisation. Elles ne sont pas des cadavres, mais bien des

esprits possesseurs. Avec un rire soudain, et un brusque saut de côté,

elles se jouent du spécialiste qui s'imagine les avoir épinglées sur son

tableau synoptique. Ce qu'elles exigent de nous ce n'est pas de monologue

d'un officier de police judiciaire, mais le dialogue d'une conversation

vivante."

-

non-abstraction

: egyptologists are aware the cognitive abilities of the Ancient

Egyptians were not the same as the Greeks. Thanks to Piaget's description of

the genesis of cognition, we can assess the Egyptian heritage with the

standards of ante-rational thought, to wit : the mythical, pre-rational and

proto-rational modes of thoughts, each having its specific modus

operandi. Hence, when we try to interprete a text, the question before us is

: in what mode or modes of thought was this written (which kind of text is

this) ? Indeed, because of the multiplicity of approaches, the Ancient

Egyptians left old strands of thought intact, with an amalgam of approaches

placed next to each other without interference as a result ;

-

spatial

semantics : Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic writing was more than a way to

convey well-formed meaning (i.e. language), but tried to invoke the magic of

the "numen praesens", involving the use of artistic space (a contemporary

equivalent is the Zen garden) as a additional element in the composition of

meaning. The Shabaka Stone, is

only one (late) example of the principles of spatial organization which

governed Egyptian from the start (besides honorific or graphic

transpositions). Unsightly gaps and disharmonious distributions were

rejected. Groupings always involved the use of imaginary squares or

rectangles ensuring the proportioned arrangement. This allowed for slight

imperfections. Furthermore, important hieroglyphs were given their

architectonic, monumental or ornamental equivalent. Spatial semantics was at

work in large monumental constructions as well as in small stela or tiny

juwelery and important tools (for Maat is at work in both the big and the

small) ... Egyptologists have not given this aspect of Egyptian "sacred

geometry" the attention it deserves (besides

Schwaller

de Lubicz), leaving the horizon wide opened to wild stellar, historical

& anthropological speculations.

-

metaphorical

inclination : Ancient Egyptians "spoke in images". This holds true

in a linguistic sense (namely their use of pictograms), but also with regard

to their literary inclinations. When somebody grabbed his meat violently,

the Egyptian thought of the voracious crocodile who has no tongue and who

has to grab his food with his teeth and swallow it in one piece. When they

saw the Sun rise and heared the baboons sing, they associated this activity

with praise and the glorification of light, etc. Some hymns speak in images,

poetical phrases, metaphors and other sophisticated literary devices.

Literary and metaphorical meaning overlapped and interpenetrated (for

example : "He who spits to heaven sees his spittle fall back on his

face.) ... The epithets of the deities too are full of visual elements. Some

egyptologists tend to rewrite this to comfort the contemporary readers. This

offends the fluid nature of the texts and makes them dry and gray. The

contrary (leaving these images intact) works confusing when Egyptian

literature is new. As a function of their intention to try to really grasp

the sense, translators make a compromize between literal and analogical

renderings. I myself tend towards the analogical (which was closer to the

Egyptian way of life), leaving room for explicative notes and comments.

"The only basis we have for

preferring one rendering to another, when once the exigencies of grammar and

dictionary have been satisfied -and these leave a large margin for

divergencies- is an intuitive appreciation of the trend of the ancient

writer's mind."

Gardiner

(1925, p.5).

It goes without

saying, that all the hermeneutical rules-of-tumb in the world will not guarantee

a perfect translation, which simply does not exist. The Italian dictum

"traduttore traditore" (the translator is a traitor), is especially

true for Egyptian. As with all texts of Antiquity, large scale comparison is the

best option. Not only has the text to be contextualized, but one has to acquire

the habit of looking up the same word or expression in various contexts

across time (lexicography). But even then, one should be content with

Gardiner's view that to circumscribe sense is the best one can do.

"Although we can approach its grammar in an orderly fashion (...) we are

often puzzled and even frustrated by the continual appearance of exceptions to

the rules. Middle Egyptian can be especially difficult in this regard ..."

Allen

(2001, p.389).

So the best one can do, given these difficulties -which can not be taken

away- is to publish the original hieroglyphic text along with new translations,

influenced as they are by consulting the original texts along with those of the

most published specialists at work in the field for the last century, i.e.

people like

Breasted,

Sethe,

Gardiner,

Faulkner,

Lichtheim,

Allen,

Hornung,

Assmann,

Grimal

and other

dedicated

contemporary scholars. In this way, alternative translations can be made by

the competent sign interpreter. This process is unending. I wholeheartedly admit

to be an amateur compared with professional linguists like Gardiner, Lichtheim

or Allen. But to gain a good understanding of the context and its problem (the

reason why the original text had to be invoked), the amateur has to know

all available linguistic tools well enough to identify a possible rule at work,

and he must have the time to think all possible solutions over many times to

"untie the knot" ...

|

initiated : 2003 -

last update : 27 XI 2010

©

Wim van den Dungen

|

|