Hermes the

Egyptian

the impact of Ancient Egypt on Greek Philosophy

against Hellenocentrism, against Afrocentrism

in defence of the Greek Miracle

Section 1

the influence of Egyptian thought on

Thales, Anaximander & Pythagoras

Section 2

Alexandro-Egyptian Hellenism & Hermetism

by Wim van den Dungen

Introduction

Section 1

the influence of Egyptian thought on

Thales, Anaximander & Pythagoras

1

Egypt between the end of the New Kingdom and the rise of Naukratis.

-

1.1

The political situation in the Third Intermediate Period.

-

1.2 A

few remarks concerning the Late Period.

-

1.3 Greek

trade, recontacting & settling in Egypt.

2 Greece

before Pharaoh Amasis.

-

2.1

Short

history of Ancient Greece.

-

2.2

The invention of the "phoinikeïa" for both vowels

& consonants.

-

2.3 Archaic

Greek literature, religion & architecture.

3

Memphite thought and the birth of Greek philosophy.

-

3.1

The origin of Greek philosophy : Thales, Anaximander

& the colonizations.

-

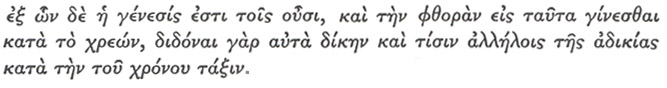

3.2

The Stela of Pharaoh Shabaka and Greek philosophy.

-

3.3

Pythagoras of Samos : the

mystery of the holy & sacred decad.

-

3.4

The Greek pyramidion or the completion of Ancient thought.

Section 2

Alexandro-Egyptian Hellenism & Hermetism

4

The Greeks in Egypt.

-

4.1 Egyptian civilization

after the New Kingdom.

-

4.2

The Ptolemaic Empire

-

4.3 Elements of the pattern of exchange between Egyptian and Greek culture.

-

4.4 Religious syncretism & stellar

fatalism.

5

The Alexandrian "religio mentis" called "Hermetism".

-

5.1 Formative

elements of Hermetism.

-

5.2

"Nous" and the Hellenization of the divine triads.

-

5.3 The

influence of Alexandrian Hermetism.

-

5.4

Crucial differences between Hermes and Christ.

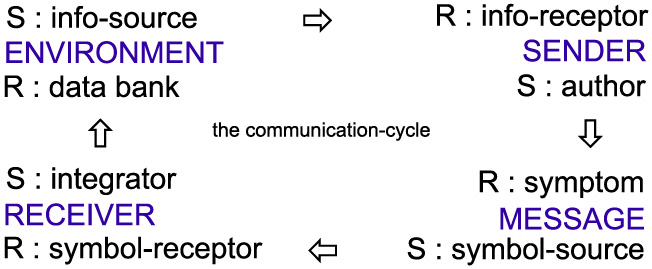

Introduction

The direct influence of Ancient Egyptian

literature on Archaic Greece has never been fully acknowledged. Greek philosophy (in particular of the Classical Period)

has -especially since the Renaissance- been understood as an excellent standard sprung

out of the genius of the Greeks, the Greek miracle. Hellenocentrism was and still is a powerful

view, underlining the intellectual superiority of the Greeks and hence of all

cultures immediately linked with this Graeco-Roman heritage, such as

(Alexandrian)

Judaism, (Eastern)

Christianity but also

Islam (via Harran and the

translators). Only recently, and thanks to

the critical-historical approach,

have scholars reconsidered Greek Antiquity, to discover the "other"

side of the Greek spirit, with its popular Dionysian and elitist Orphic

mysteries, mystical schools (Pythagoras), chorals, lyric poetric, drama, proze and tragedies.

Nietzsche, who noticed the recuperation of Late Hellenism by the Renaissance and

the Age of Enlightenment, simplistically divided the Greek spirit into two antagonistic

tendencies : the Apollinic versus the Dionysian. For him, Apollo was a metaphor

for the eternalizing ideas, for the mummification of life by concepts, good

examples and a life "hereafter", "beyond" or "out there". Dionysius was the will to live in the

present so fully & intensely as possible, experiencing the "edge"

of life and making an ongoing choice for that selfsame life, without using a

model that fixated existence in differentiating categories. A life here and now,

immanent and this-life.

And what about Judaism ? The author(s) of the Torah avoided the confrontation with the

historical fact that Moses, although a Jew, was educated as an Egyptian, and identified

Pharaoh with the Crocodile, who wants all things for himself. However, the Jews

of the Septuagint, the Second Temple and the Sacerdotal Dynasties were

thoroughly Hellenized, and they translated "ALHYM" (Elohim) as

"Theos", thereby confusing

Divine bi-polarity (kept for the

initiates). It is precisely this influence of Greek thought on Judaism which

triggered the emergence of revolutionary sects (cf. Qumran), solitary desert

hermits and spirito-social communities, seeking to restore the

"original" identity of the Jewish nation, as it had been embodied

under Solomon (and the first temple), and turned against the Great Sanhedrin of

the temple of Jeruzalem.

Ancient Egyptian civilization was so grand, imposing and strong, that its impact

on the Greeks was tremendous. In order to try to understand

what happened when these two cultures met, we must first sketch the situation of

both parties. This will allow us to make sound correspondences.

"Herodotus and other Greeks of the fifth century BC

recognized that Egypt was different from other 'barbarian' countries. All

people who did not speak Greek were considered barbarians, with features

that the Greeks despised. They were either loathsome tyrants, devious

magicians, or dull and effeminate pleasure-seeking individuals. But Egypt

had more to offer ; like India, it was full of old and venerable wisdom."

-

Matthews & Roemer, 2003, pp.11-12.

What exactly did the Greeks incorporate when visiting Egypt ? They surely

witnessed (at the earliest in ca. 570 BCE, when Naukratis became the channel through which

all Greek trade was required to flow by law) the extremely wealthy

Egyptian state at work and may have participated, in particular in the

areas they were allowed to travel, in the popular festivals and feasts

happening everywhere in Egypt (the Egyptians found good religious reasons

to feast with an average of once every five days).

In his Timaeus (21-23), Plato (428/427 - 348/347 BCE) testified the Egyptian priests of Sais of Pharaoh Amasis

(570 - 526 BCE) saw the

Greeks as young souls, children who had received language only recently

and who did not keep written records of any of their venerated (oral) traditions.

In the same passage of the Timaeus,

Plato acknowledges the Egyptians seem to speak in myth,

"although there is truth in it." According

to a story told by Diogenius Laertius (in his The Lives of the Philosophers, Book VIII), Plato bought a book from a Pythagorean called Philolaus when he

visited Sicily for 40 Alexandrian Minae of silver. From it, he copied the

contents of the Timaeus ... The Greeks, and this is the hypothesis

we are set to prove, linearized major parts of the Ancient Egyptian

proto-rational mindset. Alexandrian Hermetism was a Hellenistic blend of

Egyptian traditions, Jewish lore and Greek, mostly Platonic, thought.

Later, the influence of Ptolemaic Alexandria on all spiritual traditions

of the Mediterranean would become unmistaken. On this point, I agree with

Bernal in his controversial Black Athena (1987).

"In the first place we find the survival of

Egyptian religion both within Christianity and outside it in heretical sects

like those of the Gnostics, and in the Hermetic tradition that was frankly

pagan. Far more widespread than these direct continuations, however, was the

general admiration for Ancient Egypt among the educated elites. Egypt, though

subordinated to the Christian and biblical traditions on issues of religion

and morality, was clearly placed as the source of all 'Gentile' or secular

wisdom. Thus no one before 1600 seriously questioned either the belief that

Greek civilization and philosophy derived from Egypt, or that the chief ways

in which they had been transmitted were through Egyptian colonizations of

Greece and later Greek study in Egypt." -

Bernal,

1987, p.121, my italics.

Recently, Bernal has advocated a "Revised Ancient Model". According to

this, the "glory that is Greece", the Greek Miracle, is the product

of an extravagant mixture. The culture of Greece is somehow the outcome of

repeated outside influence.

"Thus, I argue for the establishment of a 'Revised

Ancient Model'. According to this, Greece has received repeated outside

influence both from the east Mediterranean and from the Balkans. It is

this extravagant mixture that has produced this attractive and fruitful

culture and the glory that is Greece." -

Bernal, in

O'Connor & Reid, 2003, p.29.

Bernal apparently forgets that Greek recuperation is also an overtaking of ante-rationality by

rationality, a leaving behind of the earlier stage of cognitive development (namely

mythical, pre-rational and proto-rational thought). The Greeks had

superior thought, and this "sui generis". Hence, Greek civilization

cannot be seen as the outcome of an extravagant mixture. The mixture was

there because the Greeks were curious and open. They linearized the grand

cultures of their day, and Egypt had been the greatest and oldest culture.

"Most of the names of the gods may have arrived in

Greece from Egypt, but by Herodotus' own day, as a result of receiving

gods from other peoples (Poseidon from the Libyans, other gods from the

Pelasgians and so on), the Greeks have clearly overtaken the Egyptians in

their knowledge of the gods, if they have not indeed discovered all the

gods worth discovering." -

Harrison, in

Matthews & Roemer, 2003, p.153.

On the one hand, Greek thinking successfully escaped from the contextual

and practical limitations imposed by an ante-rational cognitive apparatus unable to work

with an abstract concept, and hence unable to root its conceptual

framework in the "zero-point", which serves as the beginning of

the normation "here and now" of all possible coordinate-axis, which

all run through it (cf.

transcendental

logic). The mental space liberated by abstraction, discursive

operations and formal laws was "rational", and involved the

symbolization of thought in formal structures (logic, grammar), coherent (if not

consistent) semantics (linguistic & technical sciences) and efficient pragmatics

(administration, politics, socio-economics, rhetorics).

Because of the Greek miracle of abstraction, rationality and ante-rationality

were distinguished, equating the latter with the "barbaric" (i.e.

coming from "outside" Greece and its colonies) or

seeking the inner meaning of Egyptian religion (i.e. the wise men who studied

in Egypt and later the infiltration of Greeks in the administrative,

scribal class). Although the inner sanctum of the temples of Ptah, Re and

Amun must have remained closed (excepts perhaps for exceptional Greeks

like Pythagoras), the Greeks adapted to and rapidly assimilated

Egyptian culture and its environment.

"In addition to the tangible exchange of objects and good, from the time

of Solon there appears to have been a certain kind of abstract

intellectual contact. There survive a growing number of works written in

Greek which demonstrate some measure of familiarity with Egypt and

Egyptian thought or at least claim to have been influenced by them. The

list of authors of such works is impressive : Solon, Hecataeus of Miletus,

Herodotus, Euripides and Plato to name only the best known." -

La'ada, in

Matthews & Roemer, 2003, p.158.

On the other hand, the Greeks had no written traditions and so no

extensive treasurehouse of ante-rational, efficient knowledge (no logs).

They had no libraries like the Egyptians. In their Dark Age, literacy had

dropped dramatically and only in Ionia and Athens could pieces of Mycenæan

culture be detected. The old language (Linear B) was lost. At the

beginning of the so-called Archaic Period (starting ca.700 BCE), the

Greeks could not erect temples, had a new alphabet adapted from the

Phoenicians, no literature and very likely an oral culture, containing

legends, stories about the deities and grand, heroic deeds (such as recorded by

Homer & Hesiod, ca.750 BCE).

When their abstracting, eager and young minds got

in touch with the age old cultural activity of the Egyptians, the encounter was

very fertile, enabling the Greeks to develop their own intellectual &

technological skills, and move beyond the various examples of Egyptian

ingenuity. They were able to deduce abstract "laws" (major),

allowing for connections to be made beyond the borders of context and

action (minor) and the application of the general to the particular

(conclusion). Moreover, the rich

cosmogonies of Egyptian myth, the

transcendent

qualities of Pharaoh, the moral depth of Egypt's

sapiental discourses and

the importance of verbalization in the Memphite and

Hermopolitan schools

were readapted and incorporated into Greek philosophy, as so many other

connotations and themes, adapted by their Greek authors to their Helladic taste.

This complex interaction between Greeks and Egyptians before and under the

Ptolemies, allowed Alexandria to become a major intellectual centre, home

of native Egyptians, Greek priests & scientists, Jewish scholars,

Essenes and Hermetics alike. It continued to be influential until the

final curtain came down on it in 642 CE, when general Amr Ibn Al As

conquered Egypt for Caliph Omar, the second of the Islam's Four Pillar Caliphs.

And so nearly nine hundred years of Graeco-Roman suzerainty had come to an

end.

1.

Egypt between the end of the New Kingdom and the rise of Naukratis.

1.1 The political situation

in the Third Intermediate Period.

-

Third Intermediate Period (ca. 1075 - 664

BCE) : Dynasties XXI - XXV

-

Late Period (664 BCE - 332 BCE) :

Dynasties XXVI - XXX

-

Ptolemaic Period (305 - 30 BCE)

-

Roman & Byzantine Period (30 BCE - 642 CE)

The "golden" New Kingdom ended (ca.1075 BCE) with a weak Pharaoh.

Politically, we witness a clear division between the North (Tanis) and the South

(Thebes). Theologically, "Amun is king" ruled, and so Egypt was a

theocracy (headed by the military). In the period which followed, the Third Intermediate

Period (ca. 1075 - 664 BCE), Nubia and

the eastern desert were lost again (as well as the northern "Asiatic" regions).

At the end of this period and for the first time since 3000 BCE, Egypt lost its

independence.

The last Pharaoh of the New Kingdom, Ramesses XI (ca. 1104 -1075 BCE) had been

unable to halt the internal collapse of the kingdom, which had already filled

the relatively long reign of Ramesses IX (ca. 1127 - 1108 BCE). Tomb robberies

(in the Theban necropolis) were now discovered at Karnak. Famine, conflicts and

military dictatorship were the outcome of this degeneration. With the death of

Ramesses XI, the "golden age" of Ancient Egyptian civilization had formally come

to a close.

Dynasty XXI, founded by Pharaoh Smendes (ca. 1075 - 1044 BCE), formally

maintained the unity of the Two Lands. But his origins are obscure. He was

related by marriage to the royal family. In the North (Tanis) as well as in

Thebes, Amun theology reigned (the name of Amun was even written in a

cartouche), but in practice, the Thebaid was ruled by the high priest of Amun.

The daughter of Psusennes I (ca. 1040 - 990 BCE), called Maatkare, was the first

"Divine Adoratice" or "god's wife", i.e. the spouse of

Amun-Re, the "king of the gods". She inaugurated a "Dynasty" of 12

Divine Adoratices, ruling the "domain of the Divine Adoratrice" at

Thebes, until the Persian invision of 525 BCE.

From the XXIII Dynasty onward, the status of the

"god's wife" began to approach that of Pharaoh himself, and in the

XXVth Dynasty these woman appeared in greater prominence on monuments, with their names

written in royal cartouches. They could even celebrate the Sed-festival, only

attested for Pharaoh ! All this points to a radically changed conception of

kingship, which became a political function (safeguarding unity) deprived of its

former "religious" grandure and importance (Pharaoh as "son of

Re", living in Maat). Indeed, all was in the hands of Amun and Amun's wife

was able to divine the god's wish and will ...

Stone sculpture on a grand scale was rare. But work of unparalleled beauty &

excellence was made on a modest scale (metal, faience). But

in the North (Tanis), matter were not univocal either. Libyan tribal chieftains had been

indispensable to the the Tanite kings, but with Pharaoh Psusennes II (ca. 960 -

945 BCE), they lost their power to them ...

With Dynasty XXII ("Bubastids" or "Libyan"), founded by the Libyan Shoshenq I

(ca. 945 - 924 BCE), Egypt came under the rule of its former "Aziatic"

enemies. However, these Libyans had been

assimilating Egyptian culture and customs for already several generations now, and

so the royal house of Bubastid did not differ much from native Egyptian kingship, although Thebes hesitated.

After the reign of Osorkon II (ca. 874 - 850 BCE), a steady decline set in. In

Dynasty XXIII (ca. 818 - 715 BCE), the house of Bubastids split into two

branches.

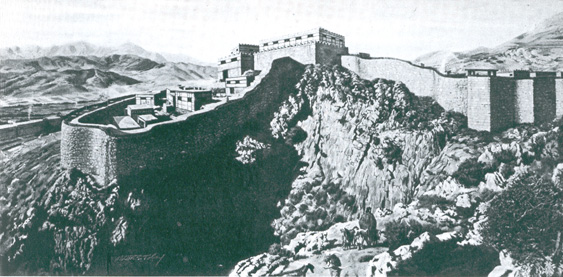

In the middle of the 8th century BCE, a new political power appeared in the

extreme South. It had for some generations been building up an important kingdom from

their center at Napata at the 4th cataract. These "Ethiopians"

(actually Upper Nubians) felt to be Egyptians in culture

and religion (they worshipped Amun and had strong ties with Thebes). The first king of this Kushite kingdom was

Kashta, who initiated Dynasty XXV, or "Ethiopian", characterized by

the revival of archaic Old Kingdom forms (cf.

Shabaka

Stone) and the return of the traditional funerary practices. Indeed, because

they possessed the gold-reserves of Nubia, they were able to adorn empoverished

Egypt with formidable wealth.

Piye (ca. 740 - 713 BCE), probably Kashta's eldest son, was crowned in the temple of Amun at

Gebel Barkal (the traditional frontier between Upper Egypt and Lower Nubia), as "Horus,

Mighty Bull, arising in Napata". He went to Thebes to be acknowledged

there. After having consolidated his position in Upper Egypt, Piye returned to

Napata (cf. "Victory Stela" at Gebel Barkal).

At the same time, in Lower Egypt, a future

opponent, the Libyan Tefnakhte ruled the entire western Delta, with as capital Sais (city of the

goddess Neit, one of the patrons of kingship). Near Sais were also the cities of

Pe and Dep (Buto), of mythological importance since the earliest periods of Egyptian history,

and cult centre of the serpent goddess

Wadjet, the Uræus protecting Pharaoh's

forehead.

When the rulers of Thebes asked for help, Piye's armies moved northwards. When

he sent messengers ahead to Memphis with offers of peace, they closed the gates

for him and sent out an army against him. Piye returned

victoriously to Napata, contenting himself with the formal recognition of his

power over Egypt, and never went to Egypt again. But the anarchic disunity of the many

petty Delta states remained unchanged.

Pharaoh Shabaka (ca. 712 - 698 BC), this

black African "Ethiopian", also a son of Kashta, was the first Kushite

king to reunite Egypt by defeating the

monarchy of Sais and establishing himself in Egypt. Shabaka, who figures in Graeco-Roman sources as a semi-legendary figure, settled

the renewed conflicts between Kush and Sais and was crowned Pharaoh in Egypt,

with his Residence and new seat of government in Memphis. Pharaoh Shabaka modelled

himself and his rule upon the Old Kingdom.

The first Assyrian king who turned against Egypt -that had so often supported

the small states of Palestine against this powerful new world order- was Esarhaddon (ca.

681 - 669 BCE). For him, the Delta states were natural allies, for -in his view-

they had

reluctantly accepted the rule of the Ethiopians. Between 667 and 666 BCE, his

successor Assurbanipal conquered Egypt (Thebes was sacked in 663 BCE) and this

Assyrian king placed Pharaoh Necho I (ca. 672 - 664) on the throne of Egypt.

With him, the Late Period was initiated.

►

Conclusion :

In the Third Intermediate Period, or post-Imperial Era, we witness the decentralization of Egypt, and

the reemergence of new divisions, either between Tanis and Thebes or

between Sais and Napata. After the XXIth Dynasty, the former "enemies of

Egypt" ruled, i.e. the Libyans and Nubians (both used as mercenaries at the

beginning of the New Kingdom).

However, we cannot say these fully

egyptianized Libyan or Ethiopian rulers destroyed Egyptian culture, quite on the

contrary. They were proud to stand at the head of Egypt, to prove to the

traditional pantheon that their rule favored them and they Egypt (so that the

deities of Egypt would remember them). Indeed, just before and after the Assyrian conquest, Dynastic

Rule was characterized by a revival of archaic Egyptian forms.

The extraordinary wealth of Egypt was monumentalized on a grand scale by artist

and architects who were also state-funded archeologists of Egyptian culture.

They studied the papyri in the various "Houses of Life" and rediscovered the old

canon. They copied "worm-eaten" documents to make them better than before. For

in their minds, the Solar Pharaohs of old were the true foundation of Egyptian

Statehood (Old Kingdom nostalgia can also be found in the New Kingdom).

1.2 A few remarks concerning the Late Period.

The XXVIth or "Saite" Dynasty (664 - 525 BCE) installed by Assurbanipal, allowed

for the resurgence of Egypt's unity and power. Necho I was killed by the Nubians

in 664 BCE and his son Psammetichus I (664 - 610 BCE) was an able stateman. He

was trusted by the Assyrians and left alone by the "Ethiopians". Because the

Assyrians could not maintain their military presence in Egypt, Pharaoh was able

to reunite Egypt. He immediately revitalized the Egyptian form by relying on the

vast cultural heritage and its recorded memory. A short renaissance saw the

light. And also in this period, the Greeks recontacted the Egyptians for the

first time since generations. Carians and Ionians were enlisted by Pharaoh, who

made his scribes study Greek.

"Saitic Egypt, with her turning back to the great

pharaonic times and her consciousness of a great cultural past, the memory of

which reaches back to a time long forgotten ("Saitic Renaissance", Assmann,

2000), is seen as the teacher of knowledge and wisdom, for she is recognized for

her old age and for her wisdom that derives from that antiquity. It seems to be

especially this "cultural memory" (Assmann, 2000) of Saitic Egypt that

determines the image of Egypt in later Greek generations." -

Matthews & Roemer, 2003, pp.14.

The Saite Dynasty sought to maintain the great heritage of

the Egyptian past. Ancient works were copied and mortuary cults were revived.

Demotic became the accepted form of cursive script in the royal chanceries.

These Pharaohs focused on keeping Egypt's frontiers secure, and moved far into

Asia, even further than the New Kingdom rulers Thutmose I and III.

When Cyrus the Great of Persia ascended the throne in 559 BCE, Pharaoh Ahmose II

or Amasis (570 - 526 BCE) was left with no other option than to cultivate close

relations with Greek states to prepare Egypt for the Persian invasion of 525.

The latter led to the defeat and capture of Psammetichus III (526 - 525) by

Cambyses (who died in 522 BCE).

Under Persian rule (525 - 404 BCE), Egypt became a satrapy of the Persian

Empire. The Persians left the Egyptian administration in place, but some of

their rulers, like Cambyses and later Xerxes (486 - 465 BCE) disregarded temple privilege.

The gods and their priests were humiliated. Only Darius I (522 - 486 BCE)

displayed some regard for the native religion. When

Darius II died (404 BCE), a Libyan, Amyrtaios of Sais, led an uprising and again

Egypt would enjoy a relatively long period of independence under "native"

rulers, the last of which being Pharaoh Nektanebo II (360 - 343 BCE).

A second Persian invasion (343 BCE) ended these short

Dynasties (28, 29 & 30, between 404 - 343 BCE). But with Alexander the Great

(entering Egypt in December 332 BCE), Egypt came under Macedonian rule. The

Greeks respected Egypt and its gods and Greek communities had been living there

for generations. In 305, the Ptolemaic Empire was

initiated (it ended in 30 BCE). Mass immigration happened : Greeks,

Macedonians, Thracians, Jews, Arabs, Mysians and Syrians settled in Egypt,

attracted by the prospect of employment, land and economic opportunity. Foreign

slaves and prisoners of war were brought to Egypt by the new rulers.

Between 30 BCE and 642 CE, Egypt was ruled by

the Romans and the Byzantines, before it became Islamic as it still is today.

1.3 Greek

trading, recontacting & settling in Egypt.

Old Kingdom Egypt used mercenaries in military expeditions.

Nubians settled in the late VIth Dynasty in the southernmost nome of Elephantine

and were employed in border police units.

"Contact with Minoan Crete and the Mycenaean Greeks is

well attested. The image of Egypt is already firmly established in the Homeric

poems and a plethora of Egyptian artefacts has been unearthed in Greece, the

Aegean and even in western Greek colonies such as Cumae and Pithecusa in Italy

from as early as the eighth century." -

La'ada, in

Matthews & Roemer, 2003, p.158.

The presence of Libyans and

Nubians is attested in the armies of Pharaohs Kamose and Ahmose at the

start of the New Kingdom. An alliance between the Hyksos Dynasty and the Minoans

existed.

"In return for protecting the sea approaches to

Egypt, the Minoans might have secured harbour facilities and access to those

precious commodities (especially gold) for which Egypt was famous in the outside

world." -

Bietak, M.,

1996, p.81.

With Pharaoh Ahmose (ca. 1539 - 1292 BCE), Minoan culture

enters

Egyptian history. Indeed, in the aftermath of the sack of

Avaris (Tell el-Dab'a - ca. 1540 BCE), the capital of the Hyksos in the Second

Intermediate Period (ca. 1759 - 1539 BCE), the fortifications and palace of the

last Hyksos king (Khamudi) were systematically destroyed. Pharaoh Ahmose

replaced them with short lived buildings reconstructed from foundations

and fragments of wall paintings of the ruins. The fragments were found in dumps to level

the fortifications

& palatial structures of Ahmose. These paintings were Minoan !

Their presence, 100 years

earlier than the first representations of Cretans in Theban tombs and earlier

than the surviving frescos at Knossos, whose naturalistic subject matter they

share, shows the cultural links between Crete and Egypt (before and

after the sack of Avaris). These frescos

seem to owe little to Egyptian tradition and serve a ritual purpose : bull-leapers,

acrobats and the motives of the bull's head and the labyrinth point to Early Cretan

religion.

As a small amount of Minoan Kamares ware pottery was found in

XIIIth Dynasty strata (Middle Kingdom), it is not impossible Egyptian

artistic style influenced Crete as far back as the Old Kingdom (jewels). These

early periods do not evidence the systematic immigration of Greeks. The links

between Greece and Egypt, as with many other nations, were probably foremost

economical.

We know Pharaoh Psammetichus I (664 - 610 BCE) employed Carian and

Ionian mercenaries in his efforts to strengthen his authority (ca. 658 BCE)

against the Assyrians. He also put some boys into the charge of the Greeks, and

their learning of the language was the origin of the class of Egyptian

interpreters, and the "regular intercourse with the Egyptians" began.

He allowed Milesians to settle in Upper Egypt (not far from the capital Sais).

This was the first time Greeks were allowed to stay in Egypt.

"With the enrollment of Greek mercenaries into his

service, Egypt became more important from the Greeks' point of view than the

ruined cities of Syria." -

Burkert,

1992, p.14.

It is Herodotus who, in his Histories, informs us that camps

("stratopeda") were established between Bubastis and the sea on the

Pelusiac branch of the Nile. They were occupied without a break for over a

century until these Greek mercenaries were moved to Memphis at the beginning of

the reign of Pharaoh Ahmose II or "Amasis" (570 - 526 BCE). They were

reintroduced in the area at a later stage to counter the growing menace of

Persia (525 BCE).

The Greek inscription found on the leg of one of the colossi at Abu Simbel,

indeed indicates that mercenaries, under Egyptian command, formed one of two

corps in the army, whose supreme commander was also an Egyptian. Under Pharaoh

Apries (589 - 570 BCE), there was a revolt of mercenaries at Elephantine ...

Because the Ionians and Carians were also active in piracy, the Egyptians were

forced to restrict the immigration of Greeks, punishing infringement by the

sacrifice of the victim.

Herodotus (II.177,1) also comments that during Pharaoh Amasis, Egypt attained

its highest level of prosperity both in respect to crops and the number of

inhabited cities (indeed, an estimated 3 million people lived in Egypt). It

was under this Pharaoh that the Greeks were allowed to move beyond the

coast of Lower Egypt. Trade was encouraged and the sources, mostly Greek,

refer to trading stations such as "The Wall of the Milesians", and

"Islands" bearing names as Ephesus, Chios, Lesbos, Cyprus and Samos.

A

lot of Greek centres emerged, but the best-documented trading centre was

Naukratis on the Canopic branch of the Nile not far from Sais and with excellent

communications. It was founded by Milesians between 650 - 610 BCE (under Pharaoh

Psammetichus I). From ca. 570 BCE, all Greek trade had to move through Naukratis

by law. So, before the end of the 6th century BCE, the Greeks had their own

colony in Egypt. The travels of individual Greeks to Egypt for the purpose of

their education, as well as Greek immigration to Kemet, the "black"

land, is usually dated at the time of the Persian invasion (525 BCE). However,

it can not be excluded that Pharaoh Psammetichus I allowed Greek intelligentsia

to study in Memphis.

Summarizing Greece/Egypt chronology (all dates BCE) :

-

ca.2600 : Neolithic Crete :

first sporadic contacts with Old Kingdom Egypt (Dynasty IV) ;

-

ca.1700 : neopalatial Minoan

Crete : Mediterranean network of artistic and iconographic exchange,

communication between Minoan high culture and Egypt (XIIIth Dynasty) ;

-

ca.1530 : Hyksos ruins in

Minoan style (Avaris) are used by Pharaoh Ahmose I ;

-

ca. 670 : Pharaoh Psammetichus

I initiated the study of Greek, employed Greek mercenaries against the

Assyrians, set up a camp that stayed in the western Delta and allowed the

Miletians to found Neukratis

;

-

570 : under Pharaoh Ahmose II

(Amasis) the Greeks were allowed to travel beyond the western Delta - Neukratis became an

exclusive Greek trading centre complete with Greek temples. He cultivated close relations with Greek states to help him against the

impending Persian onslaught ;

-

525 : Egypt a satrapy of the

Persia empire, start of a more pronounced Greek immigration to Egypt ;

-

332 : Egypt invaded &

plundered by the Macedonians ;

-

305 : Egypt ruled by Greek

Pharaohs ;

-

30 : death of Queen Cleopatra

VII, the

last Egyptian ruler.

2.

Greece

before Pharaoh Amasis (before 570 BCE).

2.1 Short

history of Ancient Greece.

The earliest traces of habitation on Crete belong to the 7th millenium BCE.

Continuous Neolithic habitation have been noted at Knossos from the middle of

the fifth millenium BCE. Towards the middle of the 3th millenium BCE (ca. 2600

BCE) a peaceful immigration took place, probably from Asia Minor and Africa,

introducing the Bronze Age to Crete. Before establishing a list of historical parallels, let us summarize the

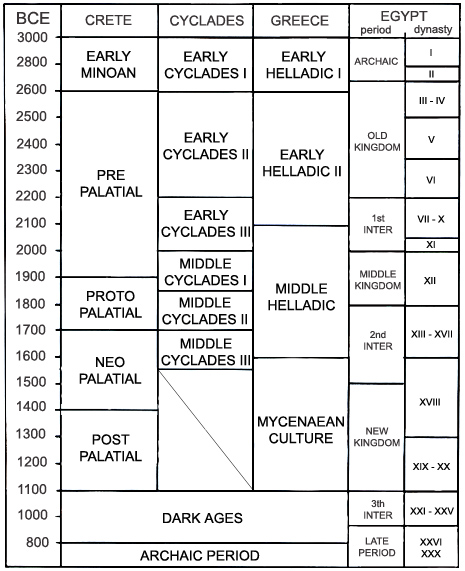

evolution of Ancient Greek culture as follows (all dates BCE) :

-

Minoan Crete (ca. 2600 -

1150) : This period is subdivided on the basis of the pottery or the

rebuilding of the palaces.

The Palatial Chronology is :

prepalatial (ca. 2600 - 1900) : The arrival of

new racial elements in Crete brought the use of bronze and strongly built

houses of stone and brick with a large number of rooms and paved courtyards,

with a varied pottery of many styles - society was organized in

"clans" ("genos"), and farming, stock-raising, shipping

and commerce were developed to a systematic level - the appearance of

figurines of the Mother Goddess - Egyptian influence at work in golden &

ivory jewels ;

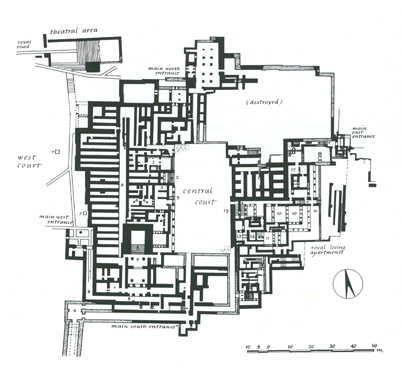

protopalatial (ca. 1900 - 1730) : Centralization

of power in the hands of kings, and the first large palace centres with wide

cultural influence : Knossos, Phaestos, Malia and Zakros (and there must

have been more) - production of very fine vases or vessels of stone and

faience, sealstones of precious or semi-precious stones, elegant weapons

& tools - the emergence of naturalistic hieroglyphic and dynamic scenes

- the pantheon has the Great Goddess as its main element as well as the use

of sacred symbols such as the sacred horns and the double axe - society is

hierarchical and contacts with the outside world become frequent -

hieroglyphic script (derived from Egyptian models ?) developed into Linear A (late

protopalatial) - a terrible disaster,

perhaps caused by earthquakes, destroyed the first palace centres ca. 1730

BCE ;

neopalatial (ca. 1730 - 1380) : Minoan civilization reached its zenith with the reconstruction of more

magnificient palaces on the ruins of the old - increase in the number of roads,

organization of the harbours, increase of trade - feudal & theocratic

society installing & maintaining the "Pax Minoica",

facilitating the cultural development of Crete - main deity is still the

Great Goddess, portrayed as a chthonic goddess with the snakes, the

"Mistress of the Animals" (lions & chamois) or the goddess of

the heavens (birds & stars), worshipped together with the god of

fertility, who had the form of a bull - the hieroglyphic script became Linear A (with two

hundred surviving texts), used until the collapse of the Pax Minoica -

in ca. 1530 the Thera

volcano on Santorini erupted - from

about 1500 onwards there was a significant increase of Mycenæan

influence - the rise of the use of a syllabic, ruling-class language, Mycenæan

Greek, now called "Linear B" (imported by the Mycenæans to Crete)

;

postpalatial (ca. 1380 - 1100) : after the final destruction of

Knossos in 1380, none of the Minoan

palaces were re-inhabited - Mycenæan

culture took over (ca. 1450) and their presence is attested both by Linear B and the appearance of typical pottery.

Ca. 1100, the descent of the Dorians heralded the demise of Minoan

civilization.

-

Helladic Age

(ca. 2800 -

1100) : This period is preceded by the Neolithical Period. The

earliest settlers reached Greece from Anatolia during the 7th millenium.

Good pasturage drew them to the plains of Thessaly or Boeotia and the land

round the gulf or Argos. They did not know the plough. The transition from

this Neolithic communites to a metal-working culture (first half of the 3th

millenium) was not always peacefully accomplished.

Following subdivisions prevail :

Early Helladic I (ca. 2800 - 2600) : Greece

inhabited by these so-called "pre-Helladics" who did not speak

Greek. At first, they lacked farming expertise. They worshipped the Mother

Goddess. Stone houses replaced mud-bricks. The Stone Age sites they erected

provided collective defence against some external threat. Trade, especially

by sea, began to flourish. Political and economical agricultural urbanism.

Local barons ruled an area of up to ten miles' radius round a walled hilltop

site.

Early Helladic II (ca. 2600 - 2100) : They

eventually capitalized and developed this progress and formed a civilized

society.

Middle Helladic (ca. 2100 - 1600) : The

arrival, in 2100 and later between 1950 and 1900, of marauding barbarians

who burnt and destroyed the fortified towns.

"Greece, at all events, like Italy, Anatolia, and

India, only came under Indo-European influence during the migrations of the

Bronze Age. Nevertheless, the arrival of the Greeks in Greece, or, more

precisely, the immigration of a people bearing a language derived from

Indo-European and known to us as the language of the Hellenes, as Greek, is

a question scarcely less controversial, even if somewhat more defined. The

Greek language is first encountered in the fourtheenth century in the Linear

B texts." -

Burkert,

1985, p.16.

These newcomers formed the

spearhead of a vast collective migrant movement originating somewhere in the

great plateau of central Asia, sweeping West and South from Russia across

the Danube and penetrating the Balkans from the North. The Greek language they

spoke was a branch of the Indo-European group (as is Vedic Sanskrit) and they are regarded as the

first, true "archaic" Greeks. The female fertility images vanished

and were replaced by a male sky-god cult and a feudal, palace-based society

akin to that of Homer's Olympians. These warrior-aristocrats were totally

unaware of seafaring and became Mediterranean traders once the slow process

of acclimatization was on its way.

Mycenæan Age (ca. 1600 -

1100) : The mythical Danaus (ca. 1600 - 1570), a Hyksos

refugee, took over Mycenæ and established the "Shaft Grave

dynasty" which lasted for several generations. Mycenæan Greece was

split up into a number of small districts (and hence to regard Mycenæ

itself as a "capital" is misleading), with a scribal caste at the

service of warrior leaders, vigorous commercial economy (based on indirect

consumption) and a high level of mostly imported craftsmanship. New were the "tholos"

burials, with their domeshaped burial-chambers. Their palaces followed the

architectural style of Crete, although their structure was more

straightforward and simple. Linear B texts reveal the names of certain gods

of the later Greek pantheon : Hera, Poseidon, Zeus, Ares and perhaps

Dionysius. There are no extant theological treatises, hymns or short texts

on ritual objects (as was the case in Crete). Their impressive tombs

indicate that their funerary cult was more developed than the Minoan.

During the mid thirteenth century (ca. 1200 - 1190) several Peloponnesian

sites suffered damage and within a century every major Mycenæan stronghold

had fallen, never to be recovered. Indeed, a vast, anonymous horde with

horned helmets and ox-driven covered wagons had made its way, locust-like,

across the Hellespont, through the Hittite Empire, by way of Cilicia and the

Phoenician coast to the gates of Egypt, to be defeated by Pharaoh Ramesses III (ca.

1186 - 1155) in two great battles. These nomadic "Dorians"

destroyed what came in touch with them, and after their defeat, they

vanished amid the wreckage of their own making. Athens never fell, and it is

unconquered Athens we have to thank for what survives of the Mycenæan

legends, although their customs vanished.

-

Dark Ages (ca. 1100 - 750)

: Over a period of nearly two centuries, beginning soon after 1100,

we find eastward migrations, from mainland Greece to the coast of Asia

Minor. These movements were driven by Mycenæan refugees, shaping a

diaspora, speaking a dialect known as Aeolic. The rich central strip of

Ionia was colonized (after a bitter struggle) after the Dorians overran

mainland Greece. About 900, the Dorians themselves spread out eastward from

the Peloponnese. Aeolic, Ionic and Doric elements intermingled. When Homer

wrote his Illiad and Odyssey (ca. 750) or Hesiod his Theogony,

the Greek world was desperately poor. The Dark Age practice of relying on a

local chieftain for protection was encouraged. Greece was a series of small,

isolated communities, clustering round a hilltop "big

house".

-

Archaic Period (ca. 750 -

478) : This period has also been called the "Age of Revolution", because after the slow recovery of the Dark Age, there

came a sudden spurt or accelerated intellectual, cultural, economical and

political efflorescence. Two divisions :

from the Dark Age to the "Greek Miracle"

(ca. 750 - 600) :

The alphabet was derived from Phoenician, but scholars differ as to when

this has happened. Some say shortly before the earliest inscriptions -found

on pottery ca. 730-, while others propose an earlier date. The latter do not

accept an illiterate Dark Age. Phoenician attained its classical form ca.

1050, and so a transmission of the alphabet in the late Mycenæan age could

not be excluded. However, by 800 there was unity in language and, to some

extent, a culture throughout the Aegean world. And in the same period as

seagoing trade resurged (ca. 750), writing was reintroduced. Thanks to the

use of a viable, fully vowelized, Phoenician-derived alphabet rather than a

restricted syllabary (Linear B), literacy became a fact. This paved the way

for the "Greek Miracle" in sixth-century Ionia.

Government was based -through hereditary aristocracy- on landownership.

Between ca. 750 and 600, we find the crystallization of the city-state and

the rise in power of the non-aristocrats, allying themselves with

frustrated noble families and putting the hereditary principle under

pressure. The two main leitmotivs of this age are discovery (literal and

figural) and the process of settlement & codification.

With Hesiod (ca.

700), the poet-farmer from Ascra, described as the forerunner of the pre-Socratics, we find a mere lay poet taking upon himself the priestly task

of systematizing myth according to the pattern of the family tree (genos).

He saw the world as a muddled, chaotic place where the only hope lay in

working out man's right relations with the gods, his fellow men and his

natural, barely controllable environment. Homeric ideals, looking back five

centuries in the past (to idealize the Mycenæan age), were swept away.

Although Hesiod betrays nostalgia for the good old days, he knows that they

are over. Those who have no power to implement their wishes, must appeal to

general principles. Hence, his morality is that of the underprivileged and

his emphasis on the omnipotent Zeus, who bestows the gift of justice ("dike").

Shortly after Hesiod, we see the rise of lyric poetry which -in the fifth

century- gave way to drama (in choral form) and to prose.

Although Homer (ca. 700) thought along paratactic (creating sentences without

subcoordinating or subordinating connectives), symbolical and

mythical lines, Hesiod did not know what an abstraction was. The idea of the

polis emerged, but was characterized by the tension between rational

progressivism and emotional conservatism, between civic ideals and ties of

consanguinity, between blood-guilt and jury justice, between old religion

and the new secularizing philosophy. Indeed, with the Ionians Thales and Anaximander of

Miletus, Greek philosophy was born

(ca. 600). Between 650 - 600 we also witness the rapidly developing

emphasis on human concerns : anthropocentrism. From about 675 onwards, the

"tyrannoi" began to seize power in the city-states all over the

Aegean world : Argos, Sicyon, Corinth, Mytilene, Samos, Naxos, Miletus and

Magara among other fell in their hands. They were an urban-based phenomenon

and were eager to promote fresh colonizing ventures.

from the "Greek Miracle" to the Classical

Period (ca. 600 - 478) :

During this period, Greece's great revolution was brought to completion. The

stiff, Egyptian stance of the male statues ("kouroi") began to

lose its hieratic formality. Politically, the slow evolution of democratic

government at Athens and the rise of Persia have to be noticed. The

predominantly "scientific" interests associated with Miletus, gave

way between 550 and 500 to a more mystically oriented movement, to which

Pythagoras, Heracleitus and Xenophanes each contributed. Between 514 and 479

all Greek history is dominated by the shadow of Persia, which contributed to

finally establish the right of mainland Greece to persue its own way of

life. A mere handful of Greek states did stand out against the gigantism of

the Persian Empire and the palace absolutism of the Near East.

During this Archaic period, pre-Socratic philosophy developed.

-

Athenian

Imperialism (478 - 404)

: With the formation of the "Delian League", Athens

broke away from the "Hellenic League", which had fought against

Xerxes. In 469, Cimon took a large fleet to the eastern Mediterranean and

routed Persia's forces. He reopened the old Levant-route to Rhodes, Cyprus,

Phoenicia and Egypt. The drift of new learning, both in the speculative as

in other fields, was firmly anthropocentric. The gods were left out or

replaced by exotic, enthusiastic and uncivic foreign cults. The

Eleusinian Mysteries were an attempt to provide this trend with some

official outlook. The Sophists emerged and pioneered the great liberal

movement, criticized by Plato. In 404, Athens at last surrendered to Sparta,

and exchanged one despotism by another.

-

Decline of the polis (404 -

323) : The next three decades, the isolationist, old-fashioned and

autocratic Spartan government ruled, triggering the formation of an

anti-Spartan coalition and Persia playing each side off against the other.

Thebes and Athens were thrown into alliance, the latter breaking Sparta's

hold on Greece. This proved a mere repetition, but under a better

leadership, of the Spartan experience. Sparta, Athens, Elis, Achaea and

Mantinea formed a coalition against Thebes. With the rise of Philip II of

Macedonia (359), the whole picture changed, and in 338 all organized

resistance to Macedonia ceased. With the death of his son, Alexander the

Great (323) a new era began (namely Hellenism). The city-states vanished and

became part of the new imperial rule.

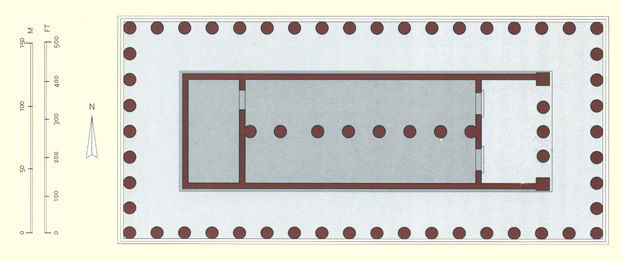

Chronological

Table of the Aegean Bronze Age compared with Ancient Egypt

This historical sketch of Ancient

Greece presents us with a lot of dynamic players and is characterized by a lot

of inner tensions and interactions with the environment (invasions, migrations,

colonizations). Natural disasters, immigration, "Doric" invasions,

Persian Wars, the Peloponnesian War and the

Macedonian rule were primordial in the formation of the Greek mentality. This

conflictual interpretation of the complexity of Greek culture explains the

extraordinary cognitive reequilibrations which happened, before but especially after

the Dark Age. This catastrophic evolution being the outer side of an inner,

mental state of discontent. It also shows the importance of cosmopolitanism, individualism, anthropocentrism

and adaptability in the formation of the Greek cultural form and its

rationality.

Using another chronological order, five fundamental stages may be discerned

-

Neolithic

Age (7000 - 2600 BCE) : settlements of farmers in Crete and mainland

Greece ;

-

Bronze

Age (2600 - 1100 BCE) : the Bronze Age, starting with the arrival of

peaceful immigrants on Crete, can be divided in two periods :

Minoan : This culture was palace-based. Between

ca. 2600 and 1600 BCE, no Greek influence was present on the island. The

Minoans reached their zenith between ca. 1730 and 1500 (the "Pax

Minoica"). Two scripts are attested : hieroglyphic (not yet deciphered)

& Linear A. The latter is nearly always used for administrative purposes

(the count of peoples & objects). The last phase of the Minoan

neopalatial civilization was characterized by Mycenæan

influence (i.e. after ca.1600 BCE).

Mycenæan : Initiated ca. 1600 BCE, the

culture of these Greek speaking people spread over mainland Greece and

reached Crete. It was strongly influenced by Minoan protopalatial (ending

with the destruction of ca. 1730 BCE) & neopalatial culture, but

remained loyal to its own Greek character. Eventually they conquered Crete

(ca. 1450 BCE) and caused the elaboration of Greek Linear B based on Cretan

Linear A, which is not a Greek language as evidenced by the few tablets

found in Linear A (for example, the word for "total" -often used in

administrative

texts- cannot be understood as the archaic matrix of a Greek

word).

So Minoan and Mycenæan cultures

interpenetraded : before 1600 BCE, Crete had directly influenced the

formation of Early Helladic Greece but was itself non-Greek (Linear A) -

after 1450 BCE, Mycenæan Greece took

over Minoan culture on Crete and Greek Linear B was used by the Minoan

treasury of Crete in the postpalatial.

-

Dark

Age (1100 - 750 BCE) : Dorian Greece, pushing Greek culture a step

back ;

-

Archaic

Age (750 - 478 BCE) : Greek culture reemerges ;

-

Classical

Age (478 - 323 BCE) : the "polis" and the emergence of classical,

conceptual rationalism.

What happened with literacy during the Dark Age ? Although it is likely

the scattered Mycenæan refugees kept some of their linguistic traditions alive,

so that some were still able to read and write Linear B, it is clear the

cultural network which had existed beforehand had been destroyed by the Dorians

and with it a unified cultural form in Greece based on a shared language. If these refugees wrote their literary texts (if any) down on tablets in Linear

B in the same way as had happened on Crete, then the reason why none were found

may be explained by the fact the clay of these tablets had been dried only

and/or reused. It is more likely though their culture was oral.

During these obscure centuries, Greek culture, as a form shared by all the

inhabitants of Greece, was nonexistent. The marauding barbarians,

who had destroyed the fortified towns of the pre-Helladics, and had developed

(thanks to Crete) into the grand Mycenæan culture, were themselves destroyed by horned plundering

hords from the North, identified by some as belonging to the Doric branch of the

Greek family ...

The length of the Dark Age (300 years) must have thrown a devastating shadow on the survival of Mycenæan

culture. Note that the name of this period refers to how little is

known about it and also points to the remarkable contrast between Doric Greece

and Mycenæan culture. Fact is the Dorians had no written language of

their own and did not use Linear B. Isolation and loss of skills

characterized the period. About the religious practices, Snodgrass (2000) says

that :

"Such practices seldom leave a substantial material

record, even in a well-documented period ; they are known to us largely from

literary sources. We should not therefore doubt the possibility of their

transmission through the dark age, simply because we cannot find proof of it in

the material evidence." -

Snodgrass, 2000, p.399.

In the memories of the few able to safeguard the original Mycenæan form,

Mycenæ became legendary and heroic. In a sense, the Mycenæans

represented the "mythical" past of the Ancient Greeks.

2.2 The invention of the "phoinikeïa" for both vowels

& consonants.

"The impact of writing as opposed to oral

culture is perhaps the most dramatic example of transformation wrought

from the outside, through borrowing." -

Burkert,

1992, p.7.

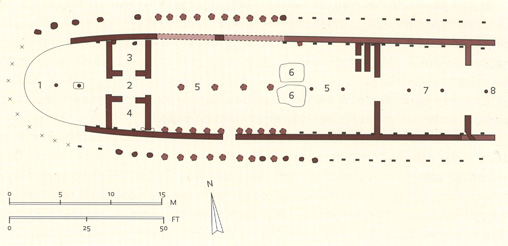

Before the reemergence of writing in Ancient Greece at the end of the

Dark Age (ca. 750 BCE), linguists distinguish between pictographic

(hieroglyphic) writing, Linear A and Linear B writing.

-

hieroglyhic script :

ca. 1900 (begin protopalatial) - 1730 BCE (destruction first palace) :

probably a Cretan, non-Greek language ;

-

Linear A : ca.

1900 - 1450 BCE (destruction second palace) : a Cretan picture-based

language which does not represent Greek words (reached its zenith

ca. 1650 BCE) - in the beginning it existed side by side with the

hieroglyphic script ;

-

Linear B :

ca. 1450 - 1380 BCE (final destruction of Knossos) : a Cretan and

Greek sound-based, syllabic language representing the archaic matrix

of Greek words - recast of Linear A ;

-

Archaic Greek

Alphabet : ca. 800 BCE : advent of one spoken language in

Greece - ca. 750 BCE : a Greek script

derived from Phoenician and adapted to Greek needs.

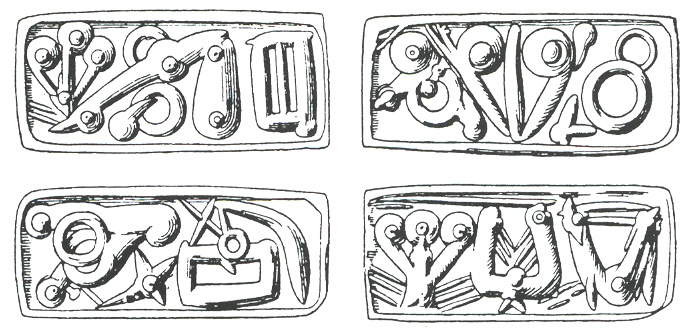

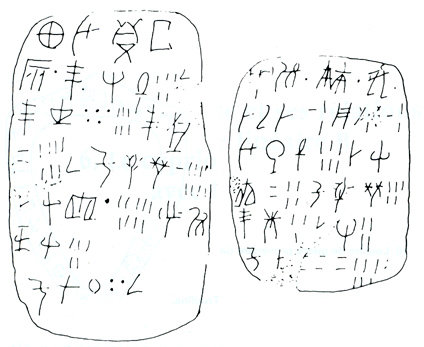

Hieroglyphic

script on seals - Crete (Lyttos)

A pictogram is the representation of a complete word (not individual letters of

phonemes) directly by a picture of the object actually denoted.

This hieroglyphic script

developed ca. 1730 BCE into Linear A. It is called

"hieroglyphic", because it resembles the signary of Old Egyptian. This

typical "pictoral narrative" can also be found on the Predynastic

Narmer Palette or the Label of Djer (Dynasty I - tomb of Hemaka).

Possibly their inspiration indeed came from Egypt, as sporadic trade was

initiated as early as the prepalatial period (during Egypt's Old Kingdom and its

Old Egyptian literature), as

evidenced in Cretan ivory & gold jewellery.

If so, then the script had various pictograms which would have received a phonetic (consonantal) and/or an ideographic value

(assisting in the determination of the meaning implied). Vowels would be absent

and the artistic, contextual placing of the signs would have played an important

role.

Next to these formal considerations, there would have been the pragmatical fact

that Egyptian hieroglyphs were "sacred" signs, only used to write down

religious, funerary, literary & philosophical thoughts of monumental &

lasting importance. The Minoans had no "cursive" form of hieroglyphic,

mostly used for secular purposes (in Egypt, this "hieratic" developed

alongside hieroglyphic, starting ca. 3000 BCE).

Indeed, Linear B seems to have

been an administrative & bureaucratic language. No linear B literature has

(yet) been found ...

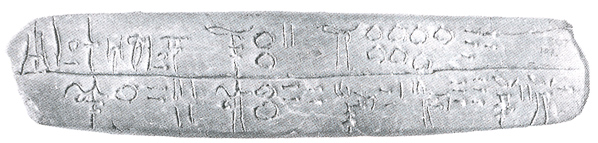

Linear

A Tablet Co 907 - Crete (Knossos)

Linear A is

mostly inscribed on stone. The shape of these signs suggests an earlier

development, but nothing can be said for sure.

Most inscriptions were found in

the south of Crete. The script was primarily used -unlike the sacred Egyptian hieroglyphs- for

administrative purposes. Linear A was in use when Egyptian had

already entered its classical, so-called "Middle Egyptian" format. Linear

A

is not a Greek language. Although phonograms may occur, Linear A is (like

the hieroglyphic script) picture-based. It also appeared in religious contexts.

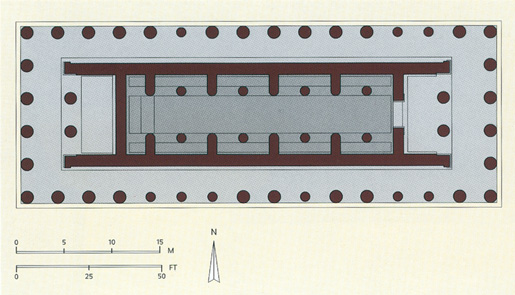

Linear

B Tablets

13 & 85 - Crete (Haghia Triada)

Linear B (derived from Linear A) is not picture-based (pictogram) but

sound-based (phonogram). A

series of 87 signs are used. The basic syllabary consists of 60 biliteral signs.

With these the phonetic value

of words are written down. The basic syllabary is the combination of 5 vowels with 12 consonants.

Linear B adds 16 optional signs and 11 signs are not yet identified. The

optional signs are used to allow one to identify words more precisely or

to represent two basic signs. It is read from left to right. Linear B

(also used in the last phase of the Minoan culture) was the script of the Mycenæns

(ca. 1600 - 1100 BCE) and its language was Greek. Archaeological evidence showed

that Linear B was not used a lot in mainland Greece. No private use of the

language has been discovered. It was deciphered by Ventris in 1951.

Apparently, Linear B was only used to keep records in Greek at Knossos and later

at the palaces of Thebes, Mycenæ

and Pylos.

"L'écriture semble avoir été employée

exclusivement comme un outil bureaucratique, le moyen indispensable de

conserver les comptes et documents administratifs, mais jamais dans une

perspective historique et encore moins profane. (...) le contenu des

tablettes en linéaire B consiste, presque sans exception, en listes

d'individus, d'animaux, de produits agricoles et d'objects

manufacturés." -

Chadwick, 1994, p.191.

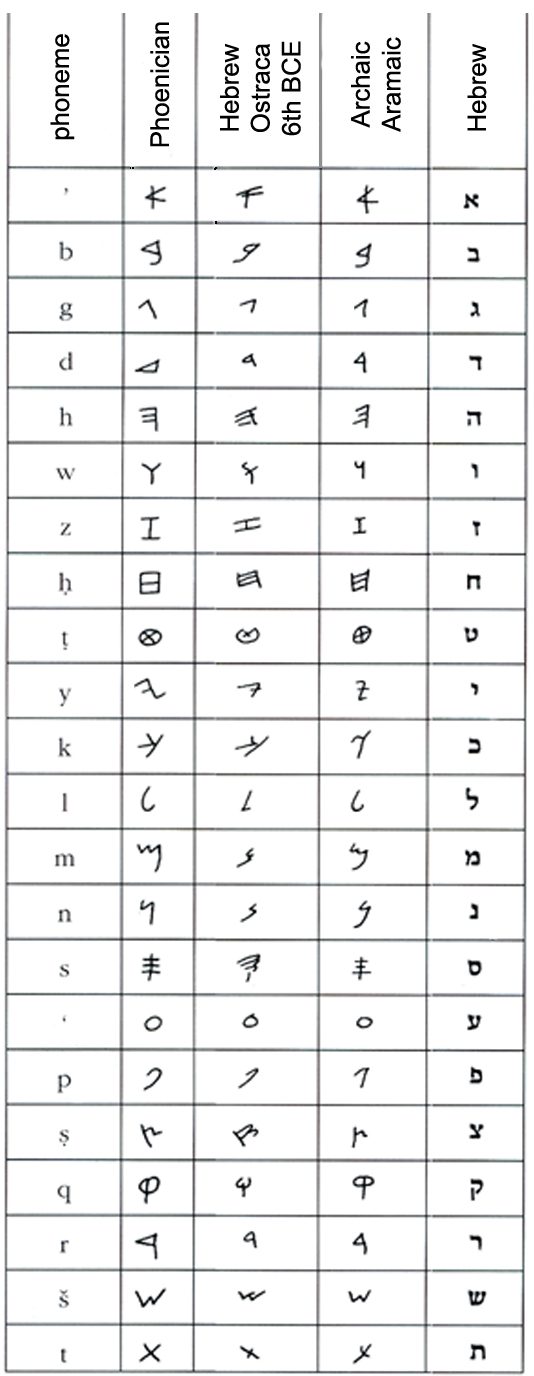

Phoenicia, its language & alphabet

Phoenician

alphabet of Byblos - ca. 1050 BCE

with Aramaic & Hebrew derivations

In Antiquity,

Phoenicia was the region corresponding to modern Lebanon, with adjoining parts of modern

Syria and Israel. Its inhabitants, the Phoenicians, were notable merchants,

traders, and colonizers of the Mediterranean in the 1st millennium BCE. Its chief

cities were

Sidon, Tyre, and Berot (modern Beirut).

It is not certain what the Phoenicians called themselves in their own

language. It appears to have been "Kena'ani" (Akkadian : "Kinahna")

or

"Canaanites." In Hebrew the word "kena'ani" has the secondary

meaning of "merchant," a term characterizing the Phoenicians well.

The Phoenicians probably arrived in the area about 3000 BCE. Nothing is known of

their original homeland, though some traditions place it in the region of the

Persian Gulf.

At Byblos,

commercial and religious connections with Egypt are attested from the IVth

Dynasty. Extensive trade was certainly

carried on by the 16th century, and the Egyptians soon established suzerainty

over much of Phoenicia. The 14th century, however, was one of much

political unrest, and Egypt eventually lost its hold over the area. Beginning in

the 9th century, the independence of Phoenicia was increasingly

threatened by the advance of Assyria,

the kings of which several times exacted tribute and took control of parts or

all of Phoenicia. In 538 BCE, Phoenicia passed under the rule of the

Persians. The country was later taken by Alexander the Great and in 64 BCE was

incorporated into the Roman province of Syria. Aradus, Sidon, and Tyre, however,

retained self-government. The oldest form of government in the Phoenician cities

seems to have been kingship limited by the power of the wealthy merchant

families. Federation of the cities on a large scale never seems to have

occurred.

The Phoenicians were well known to their contemporaries as sea traders and

colonizers, and by the 2nd millennium they had already extended their influence

along the coast of the Levant by a series of settlements, including Joppa

(Jaffa, modern Yafo), Dor, Acre, and Ugarit. Colonization of areas in North

Africa (like Carthage), Anatolia, and Cyprus also occurred at an early

date. Carthage became the chief maritime and commercial power in the western

Mediterranean. Several smaller Phoenician settlements were planted as stepping

stones along the route to Spain and its mineral wealth. Phoenician exports

included cedar and pine wood, fine linen from Tyre, Byblos, and Berytos, cloths

dyed with the famous Tyrian purple (made from the snail Murex),

embroideries from Sidon, wine, metalwork and glass, glazed faience, salt, and

dried fish. In addition, the Phoenicians conducted an important transit trade.

In the artistic products of Phoenicia, Egyptian motifs and ideas were

mingled with those of Mesopotamia, the Aegean, and Syria. Though little survives

of Phoenician sculpture, the round, relief sculpture is much more abundant.

The earliest major work of Phoenician sculpture to survive was found at Byblos :

the limestone sarcophagus of Ahiram, king of Byblos

at the end of the 11th century. Ivory and wood carving became Phoenician specialties, and Phoenician

goldsmiths' and metalsmiths' work was also well known.

Although the Phoenicians used cuneiform (Mesopotamian writing), they also

produced a script of their own. The Phoenician alphabetic script of 22 letters

appeared at Byblos ca. 1050 BCE, but earlier stages are likely. The

inscription on the sarcophagus of Ahiram (ca. 1000 BCE), shows a scripture

which had already attained its classical form. This method of writing, later

adopted by the Greeks, is the ancestor of the modern Roman alphabet. It was the

Phoenicians' most remarkable and distinctive contribution to arts and

civilization.

This writing system developed out of the North Semitic alphabet and was spread over the Mediterranean area by Phoenician

traders. It is the ancestor of the Greek alphabet and, hence, of all

Western alphabets. The

Phoenician alphabet gradually developed from this North Semitic prototype and

was in use until about the 1st century BCE in Phoenicia proper, when the language was already being

superceded by Aramaic. Phoenician

colonial scripts, variants of the mainland Phoenician alphabet, are classified

as Cypro-Phoenician (10th - 2nd century BCE) and Sardinian

(ca. 9th century BCE) varieties. A third variety of the colonial Phoenician

script evolved into the Punic and neo-Punic alphabets of Carthage, which continued to be written until about the 3rd

century CE. Punic was a monumental script and neo-Punic a cursive form. Punic

was influenced throughout its history by the language of the Berbers and

continued to be used by North African peasants until the 6th century CE.

The Phoenician alphabet in all its variants changed from its North Semitic

ancestor only in external form. The shapes of the letters varied a little in

mainland Phoenician and a good deal in Punic and neo-Punic. The alphabet

remained, however, essentially a Semitic alphabet of 22 letters, written from

right to left, with only consonants represented and phonetic values unchanged

from the North Semitic script. Phoenician is very close to Hebrew and

Moabite, with which it forms a Canaanite subgroup of the Northern Central

Semitic languages.

Phoenician words are found in Greek and Latin classical literature as well as

in Egyptian, Akkadian, and Hebrew writings. Phoenician and Hebrew scripts, both

monumental and cursive, were closely akin and developed along parallel

lines. Modern decipherment of Phoenician took place in the 18th century

(Swinton, Barthélemy). Phoenician epigraphic material is far from

impressive. the Greek adaptation of the Phoenician

alphabet

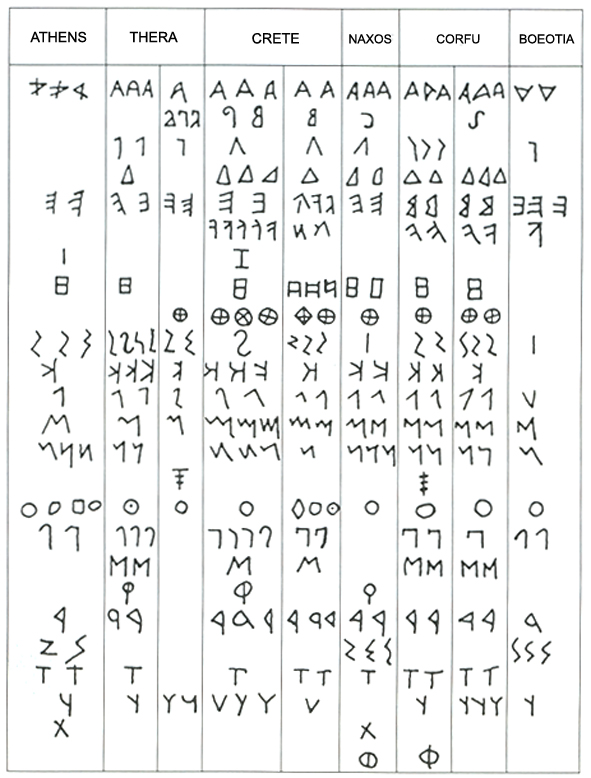

Archaic

Greek Alphabets derived from Phoenician Although

the Greeks played no important role in the formation of their own

alphabet, they added a crucial dimension : the five vowels. Indeed,

Phoenician, like Aramaic and Hebrew, was essentially a Semitic alphabet.

It consisted of 22 letters, written from

right to left, with only consonants. Semitic languages remained written from

right to left, while archaic Greek inscription had both directions before

fixating the opposite direction (from left to right). Moreover, the order

of the letters was also fundamentally Phoenician, and the Hebrew meaning

given to the individual letters corresponded with the Greek name for the

letter :

aleph / alpha (ox), beth / bèta

(house), gimel / gamma (camel), daleth / delta

(door), he / epsilon (window), vau / upsilon

(nail), zain / zèta (sword), cheth / èta

(fence), teth / thèta (serpent), yod /

iota (hand), kaph / kappa (hollow

hand), lamed / lambda (ox-goat), mem / mu

(water), nun / nu (fish), sameth / xi

(prop), ayin / omicron (eye), pe / pi

(mouth), tzaddi (fish hook), qoph (back of hand), resh / rho

(head), shin / sigma (tooth), tau / tau

(cross-mark)

Seven Phoenician consonants (cf. "phoinikeia grammata", the

"Phoenician letters") were unnecessary in Greek (identified by

their Hebrew names) : "aleph", "he", "vau",

"yod", "ayin", "tzaddi" &

"qoph".

These unnecessary consonants were used to represent the vowels and two

consonants, "tzaddi" and "qoph", were dropped. The

"vau" was taken out of the Phoenician alphabetical order and

added as "upsilon" at the end of the new Greek alphabet,

together with four typical Greek sounds.

-

the "aleph"

was used for "a" ;

-

the "he" was

used for "e" ;

-

the "vaw" was

used for "u" ;

-

the "yod" was

used for "i" ;

-

the "ayin"

was used for "o" ;

Finally, they added four

Greek sounds :

-

the "phi",

for "ph" ;

-

the "chi",

for "ch" ;

-

the "psi",

for "ps" ;

-

the "omega"

for "oo".

This alphabetic system

provided the Greeks ca. 750 BCE with 7 voweled sounds : "a",

"e", "ee", "i", "o",

"oo" and "u". The complete alphabet ensued : (a) alpha,

(b) bèta, (g) gamma,

(d) delta, (e) epsilon,

(z) zèta, (è) èta,

(th) thèta, (i or j) iota,

(k) kappa, (l) lambda,

(m) mu, (n) nu,

(x) xi, (o) omicron,

(p) pi, (r) rho,

(s) sigma, (t) tau,

(u) upsilon, (f or ph) phi,

(ch) chi, (ps), psi

and (oo) omega.

In all Ancient Semitic languages vowels were omitted. Even in Ancient

Egyptian, only the consonantal structure was recorded. Vowels are

dynamical, and constitute the variety & adaptability of a script to

concrete situations like gender, number and measurements. In Linear B,

vowels (a and o) were used to define gender and were recorded. By adding

vowels to their alphabet, the Archaic Greeks allowed the written language to

reflect the spoken one, so that a text seemed a fixating copy of the concrete,

living situation which triggered its composition (in Egypt, the difference

between the spoken word and the "sacred" hieroglyphs was

considerable). Thanks to vowels, the event could be exactely recorded, and

made present "in abstracto" as text. Hence, Greek cultural forms could

be transmitted with more precision, which triggered the formation of a

"historical memory" based on records which reflected the past as it

was (devoid of the ante-rational connotations & contexts necessary to

decipher non-voweled texts). Literacy meant thus much more than access to the

sacred (as in Egypt) : by writing down their language using a voweled alphabet,

the Greeks were able to captivate & describe the living, concrete context

in such a way that the text better represented the real or ideal thing.

In my opinion, binding vowels fits well the linearizing and defining state of

mind of the Greeks. In Mycenæan Linear B, the

system was till syllabic, joining each vowel with a consonant. In Cretan Linear

A, the pictogram ruled but phonetic value might have been present. But Linear B

offered a clear advantage : it was sound-based and fixated the vowels, though

not absolutely. With the adaptation of the Phoenician script at the

beginning of the Archaic Age, the Greeks took a fundamental cognitive step

forward and eliminated the exclusive consonantals, identifying each vowel with an

alphabetic sign of its own !

The evolution of cognition may hence be linked with these various scripts as follows (for

Ancient Egypt see : theology,

verbal

philosophy and magic)

-

hieroglyphic script :

mythical mode : loose pictograms on Creta ;

-

Linear A : mythical mode :

pictoral system ;

-

Linear B : pre-rational mode

: syllabic system with relatively fixed vowels ;

-

Archaic Greek :

proto-rational mode : alphabetic system with fixed vowels.

The fixation of the vowels in

an absolute, phonographic sense, allowed the Greeks to define a series of

categories which had remained outside the scope of any other script of

Antiquity. The vowels could be used to write down gender, verbal inflections

and suffixes making the language fluid. Suddenly, about 750 BCE, the Greeks had a tool

to define meaning

with an unprecedented precision and clarity, adapted to the spoken tongue.

This accomplishment must not have passed unnoticed when -under Pharaoh Psammetichus

I- they arrived in

Egypt. There was however no direct information

available to the Greeks about Egypt as a whole, for -as a group-

they were forced by law to remain in the western Delta, a situation which would

change when Pharaoh Amasis ascended the throne of Egypt in 570 BCE.

2.3 Archaic

Greek literature, religion & architecture.

►

at the treshold of archaic literature

At the beginning of recorded Greek

literature stand two grand epic stories, the Iliad and the Odyssey,

attributed to Homer, and the works of Hesiod (White,

1964), like the Theogony.

Some features of the Homeric poems reach far into the Mycenæan age, perhaps to 1500

BCE, but the written works are traditionally ascribed to Homer. In their

present form, they probably date to the 8th century (recorded ca. 750 BCE).

It goes without saying that the elaborated compositional framework evidenced

in these masterpieces proves the existence of an oral tradition.

"The likely conclusion is that the

Homeric political system, like other Homeric pictures, is an artificial amalgam

of widely separated historical stages. And yet there is natural and almost

irresistible urge to look for a single period in which as many features as

possible of the picture can be credibly and simultaneously set." -

Snodgrass, 2000, p.389.

Implicit references to Homer and

quotations from the poems date to the middle of the 7th century BCE.

Archilochus, Alcman, Tyrtaeus, and Callinus in the 7th century and Sappho

and others in the early 6th adapted Homeric phraseology and metre to their

own purposes and rhythms. At the same time, scenes from the epics became

popular in works of art. The pseudo-Homeric "Hymn to Apollo of

Delos," probably of late 7th-century composition, claimed to be the

work of "a blind man who dwells in rugged Chios", a reference to a

tradition about Homer himself.

The general belief that Homer was a native of Ionia (the central part of the

western seaboard of Asia Minor) seems a reasonable conjecture, for the poems

themselves are in predominantly Ionic dialect. Although Smyrna and Chios

early began competing for the honour, and others joined in, no authenticated

local memory survived anywhere of someone who, oral poet or not, must have

been remarkable in his time ...

With Hesiod, the farmer-poet from Ascra, apparently of the eighth century

BCE, described as a forerunner of the pre-Socratics, we encounter a lay poet

taking upon himself the task of systematizing myth. He saw the world as a

muddled, confusing, chaotic place where the only hope lay in the hands of the

Pantheon, one's fellow men and natural factors around him. The barely

controllable essence of the world springs to the fore. Brute necessity is more

important than Homeric ideals, and the individual emerges out of the collective

in a desperate mode. Grim might seems right here. Zeus however, has the gift of

justice ("dike") and crime does not pay. Hesiod stands midway Homer

and the Milesian philosophers.

There is no evidence to substantiate the existence of Greek literature in Linear

B, although Indo-European poetry is attested as an art form in "measured

lines with fixed poetic flourished, some of which appear in identical form in

Vedic and Greek." (Burkert, 1985, p.17, my italics).

The use of leather, combined with a sea climate, makes it unlikely to ever discover

original Mycenæan

texts. The Linear B tablets found survived because of

catastrophic fires which destroyed the buildings they were stored in (for the

original were only sun-dried). It is likely that under the Mycenæans and the Dorians,

the bulk of all Homeric and Hesiodic ideas were transmitted exclusively orally.

Let us speculate, and assume Mycenæan poets at times wrote down

a brief sketch of their works, assisting memory with small inscriptions in

Linear B on leather and sun-dried clay, and assuring the continuity of the

synopsis of their thought (combined with extensive oral training). A strong

contra-argument has always been the absence of inscriptions on pottery (instead,

geometrical forms were used). But this is apparently less significant in Greece

in terms of scriptoral capacity than it was in Ancient Egypt, with its

"magical"

and "divine" interpretation of language and its eternalization.

"... the criterion of ceramic style as an indicator

of major cultural changes is less satisfactory. We have found it misleading ..."

-

Snodgrass, 2000, p.393.

► towards Archaic

Greek religion

Minoan religion was associated with the

miracle of nature, and our principal source of knowledge are artistic

representations inspired by a deified natural world and depicting or

facilitating religious cult.

"They might be described as high-class hedonists with

a strong religious sense ; and their religion, characteristically, seems to have

been a gay open-air everyday faith, with holy spots on mountain-tops and in

groves or by springs and well-houses, with fertility goddess and an Artemis-like

Mistress of Beasts ..." -

Green,

1973, p.34.

Three important features of the Minoan religious experience stand out :

-

the

sacrality of the tree : the tree marks a sanctuary and is surrounded

by a sacred enclosure. During processions, the anthropomorphic Great Goddess

is enthroned beneath it. The same holds for pillars, columns and stones

;

-

the

chthonic powers : sacrifice of the bull (symbol of the fecundity of

nature, the male god of vegetation), bull-games, double axe and sacral horns

point to the mastering of the chthonic powers of the mother goddess, who

played a central role ;

-

the

epiphany of the deity from above in the sacred dance : it seems that

mystical communion with the god (i.e. the direct experience of the Divine)

was important and momentary scenes of epiphany show the deity besides the

sacred tree, in front of shrines, next to a stepped altar or on a mountain

peak.

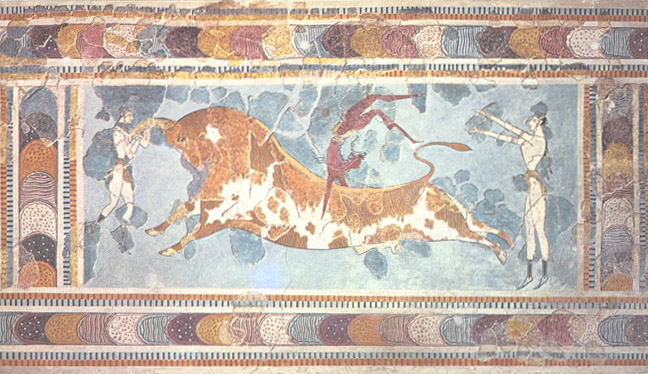

Although obvious differences are

present, Minoan and Egyptian religion are of the same family. Both are based on

nature, the exhaltation of life and divine kingship. They share identical

iconography : the bull as symbol of permanence, the sacrality of trees and

elevated places, the ample use of colorful representations of fauna and flora

and similar jewelry. On Crete, nature at times was a rumbling, bull-like

underground which knocked down their best palaces. Hence, to find and keep the

proper "equilibrium" was what was needed to allow the acrobat to jump

over the back of the bull. In Egypt, were chaotic Nile-floods could cause famine

and wreck social order, the

image of the balance

expressed a solidarity with nature, despite its darker, destructive sides.

The famous

"Bull-leaping" fresco, East wing of the palace of Knossos - 15th

century BCE